Saturday

Arts and PoetryLhadrima: Part Two of a Painter’s Journey

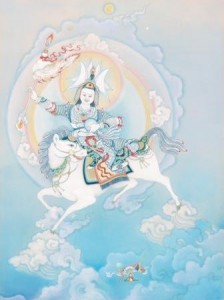

A Western Woman’s Journey as Painter of the Lha: The Noble Conquerors.

Click here for PART ONE in the Lhadrima series

By Cynthia Moku

Drawings and preliminary sketches of the buddhas, bodhisattvas, yidams, protectors and historical emanations form a large part of my process in painting a full thangka or scroll. Following the western tradition of classical visual arts, drawing remains a fundamental skill through which a painter studies her musings, records her discoveries and transforms her direct experience into authentic indelible gestures for others to “read.” Drawing is a simple situation, an honest recording with basic tools made from plant fibers, wood and lead, the paper and the pencil. When I settle in to draw, it is a time for me to become familiar with the visual impression of a buddha’s countenance: the posture, the gesture of the hands, the subtle or dynamic movements in the robes or ornaments. The finest historical works in this traditional iconography convey a clarifying equilibrium inherent in the figure, subtly coming forth from an even and centered alignment. Such a well-drawn graphic example serves as a mirror to a meditator’s visual perception in the use of these paintings for creation- and completion-stage meditation practices.

This countenance or expressive narrative of a buddha’s body and surrounding field comprises a consistent and significant aspect of Buddhist iconography, whether the Buddha’s distinctive manifestation is calm or dynamic. The artist adheres to encompassing these aspects of enlightened qualities through compositional symmetry, figurative balance and integrity of proportion. This discipline remains a fundamental characteristic within Buddhist art despite the variety of cultural influences naturally expressed throughout its history and subsequent global reach, beginning from the time and place of Prince Siddhartha-Shakyamuni Buddha’s life over 2500 years ago. Such facets in the graphic expression of the Buddha’s form are fundamental to the visual message that thangka paintings present. Viewers appreciate such a time-honored expression on three experiential levels: outer, inner and innermost. For the message to be conveyed, the artist aspires to stay present with these measures of experience while painting. To record these intangible yet essential qualities, I rely on my training in technique and my love of observation. In this way, the brush describes the details of every aspect of the image, right in the actual moments of painting. This attention to detail and atmospheric countenance moving back and forth between one another as the painting progresses becomes a spontaneous and at the same time choreographed engagement. Like a fine shimmering silken thread, the firm yet flexible anchor grounding this process calls for staying present within the precision and gentle spaciousness of a meditative mind. It is a continuous practice.

Over a lifetime of artistic endeavors, including training in Japanese brush stroke practice, I now paint combining several traditional techniques. For instance, sometimes I paint thangkas on sheer silk, which I fuse to fine-weave cotton through a process similar to mounting Japanese calligraphies on rice paper. Another example is in the continuous work I have returned to for over a decade–a series of large portrait drawings of twentieth and twenty-first century meditation masters. This series combines adherence to buddha tigse (the correct proportions of a buddha figure) while rendering portraits of the meditation masters who have been and currently are my spiritual teachers. I highlight the feeling tone of the face and hand gestures using the technique of rendering form with shades of grey related to a source of light. Surrounding each portrait are symbolic elements chosen to express the story of the particular teacher’s activity in the world. Rendering in this way challenges the artist, because the source of light in a thangka painting is always the transparent radiance of the enlightened figure itself. It is a centralized ambiance permeating the entire composition. Thus, there are no shadows in a thangka painting, since there are no shadows in a fully enlightened mind. Through these portrait studies I have found that rendering a minimally colored graphite drawing, rather than flattening form, enhances transparency of form. The resultant effect expresses the illustrative essence of enlightened manifestation through an unconventional format.The many lamas that stayed at our dharma center in San Francisco in the 1970s appreciated my drawings, and I received encouragement from them: Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, Lama Kungha Rinpoche, Sister Palmo, Kalu Rinpoche’s lamas and others. Today I am so grateful to the many teachers that continue to extend their blessings in this way. Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche, Khandro Rinpoche, Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche, and Kyabje Kobun Chino Roshi have all, at various times in direct and indirect ways, encouraged me as I continued in my non-traditional works while staying true to the practice of alignment, intention, tigse and dedication.

The Dalai Lama gave me great encouragement and a supremely humble example when he took time in his schedule to consecrate one of my thangkas that is now part of the Denver Art Museum’s permanent collection of Buddhist art. Ponlop Rinpoche soon after inscribed the thangka with his own hand. It is the first traditional vajrayana scroll painting in a major American museum that states, “Country of Origin: The United States of America.” This acquisition was supported by a patron of contemporary American art and culture.

Beginning in 2003, Sakyong Jamgon Mipham Rinpoche conferred his trust and respect in asking me to paint the Primordial Rigden thangka for the Shambhala sangha and other images central to the termas of Shambhala. After the Primordial Rigden thangka was introduced, director Johanna Lund beautifully crafted a short documentary film offering a picture of our collaboration, entitled “Realizing Confidence: The Making of the Primordial Rigden Thangka.”

Beginning in 2003, Sakyong Jamgon Mipham Rinpoche conferred his trust and respect in asking me to paint the Primordial Rigden thangka for the Shambhala sangha and other images central to the termas of Shambhala. After the Primordial Rigden thangka was introduced, director Johanna Lund beautifully crafted a short documentary film offering a picture of our collaboration, entitled “Realizing Confidence: The Making of the Primordial Rigden Thangka.”

On occasion, several rinpoches have given talks to the students of my thangka painting classes at Naropa University. Most notably, Lama Tarchin Rinpoche has generously given teachings during several semesters. With his gentle and insightful presence, he introduces them to the basic goodness of their original noble heritage and the significance of their practice in drawing the Buddha.

Learning tigse foremost in all the classes, coupled with aspiration and dedication of merit in each session, the students receive college credit for their efforts and study. This has been the format for other related projects such as the Padmasambhava statue sculpted by Thinley Norbu Rinpoche and Lama Tarchin Rinpoche situated on the hills overlooking the Kona Coast in Hawaii. Students of the Vajrayana Foundation working with resident teacher Lama Yeshe Wangmo assisted me in painting the entire sculpture, which consists of Padmasambhava’s life-size figure seated on a large lotus arising out of an ornamented pool containing blooming lotus flowers.

Kalu Rinpoche’s earlier directive became apparent in other unexpected ways. During fourteen consecutive summers between 1987and 2001, I led mural painting residencies at three large public stupas along the spine of the Rocky Mountains from northern Colorado to central New Mexico. These immense construction projects provided another opportunity for communities of practitioners to come together under one umbrella and paint images of the buddhas, the deities and their environments.

After nearly thirty-five years of guiding others in the discipline of thangka painting, I can point to quite a few genuine painter/practitioners continuing their work begun in these initial classes through Naropa University. Disciples of Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche in the Mangala Shri Bhuti sangha have particularly remained steadfast in this training. These classes continue every fall semester through studio classes, weekend painting retreats, and field trips to dharma center shrine rooms and museum collections. In the past two years I have had the additional opportunity, due to an invitation by Professor Deborah Haynes, of teaching the practice of drawing the Buddha’s face to undergraduate students at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Included at the beginning of every class session is time for shamatha meditation instruction and practice. This is a truly cool and unusual opportunity.