Sunday

Arts and PoetryLhadrima: Part Three of a Painter’s Journey

A Western Woman’s Journey as Painter of the Lha: The Noble Conquerors.

Click here for PART TWO in the Lhadrima series.

By Cynthia Moku

Painting the images of the buddhas and the bodhisattvas can become a skillful method when coupled with the path of meditation, I firmly believe. In his book, Ruling Your World, Sakyong Jamgon Mipham Rinpoche says, “With discipline, we are making a container in which we can continue to grow. Only through discipline can we truly experience our vast mind, the outer limits of our possibilities.” Joined to this fresh pervasive discipline that the Sakyong encourages is an additional benefit within the practice of thangka painting–one dedicates the merit of every period of work to the benefit of all beings. Kalu Rinpoche once said to me, “Lozang, you have a fine hand. Whatever you do, stay true to tigse and always dedicate the merit.” In those early days, I took his words very literally, studying and practicing tigse by drawing the Buddha repeatedly.

At this point in my training, I know that Kalu Rinpoche’s advice extends to every aspect of painting and drawing that I do, whether traditional or non-traditional. Even more to the point, alignment and intention are actually fundamental to all of phenomena’s display and our experience of it. To dedicate the merit of work done within a tradition that honors such fundamental “inter-being,” as Thich Nhat Hanh states, is simply pouring the wisdom into its source, refilling the vessel from which we have been thoroughly refreshed.

More recently in teachings opening the gateway to the profound Ati view of the Secret Essence Tantras that I am receiving through the supreme generosity of Khenpo Namdrol Rinpoche, the truth of tigse is being expressed beyond distances I could ever have dreamed. Made possible through the skillful translation and example of Lama Chonam and Sangye Khandro, tigse’s truth is there in the language of dharma, the teachings of the Buddha and the subsequent commentaries written by completely realized masters such as Longchen Rabjam and Mipham Rinpoche. In their refined and in-depth explanation of the rising of compassion directly from within the wisdom heart of the buddhas, I am brought back to reflect on Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche’s words describing the path of discipline. Through these profound teachings of the Sangwai Nyingpo Tantra, I realize that the outer limits of a buddha’s possibilities, their emanations, are without measure.

Thus, drawing the form of buddha according to proper tigse measurements signifies the pure expression of a buddha’s unbounded mind. Such freedom within limits, offers a link to the lineage and the recognition that the buddha’s form lacks nothing and is never static.

In the late 1980s in Boulder Colorado, while I designed and eventually initiated Naropa University’s first Bachelor of Arts Degree Program in the Visual Arts, the Vidyadhara Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s artistic eye began to spin its magic on me. I saw in his art a skillful and uniquely creative adherence to tigse. This recognition gave me great confidence in his artistic expression. His art truly embodied a performance of liberation. Inspired by this great unconventional master, I began to explore tigse in a variety of ways with the precision of the fine nearly single-haired brushes of thangka painting and with the immediacy of Japanese calligraphy brushes, both small and very large.Being introduced to, practicing, and in some instances co-teaching with colleagues at Naropa, the creative practices of mudra space awareness and the maitre rooms, ikebana, object arrangement, dharma art, stroke practice and kyudo, all informed my search. In hindsight, I see how these disciplines as presented through the supreme example of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche further polished the jewel of instruction that Kalu Rinpoche had laid before me. I became even more tigse-fied. Now, the pervasive joy of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s expressive art nudged me to explore the uncommon and intangible aspects of the elements crucial to painting an enlightened figure.

As a core faculty member of Naropa University (then, Institute), I was put on the spot to express “bone knowledge,” the truth and rawness of my experience in the moment. Non-traditional artwork began to emerge which instinctively was informed by my traditional training, both eastern and western styles and techniques. In the mid 1990s, encouraging collaboration between the faculty members that I hired specifically for the visual art degree program, I also became a student to a few of them. Eichi Okamoto Sensei led me into the refined warrior world of Japanese calligraphy and spontaneous brush stroke. He never allowed me to “learn” the language, but rather kept me facing the white space of the paper with little concept to interfere with the movement of the brush. Likewise, Joan Anderson played a particularly important role in my journey as a painter discovering the honesty in abstraction.

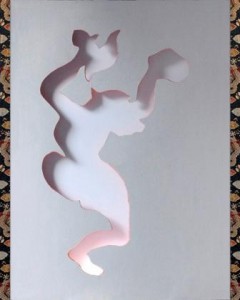

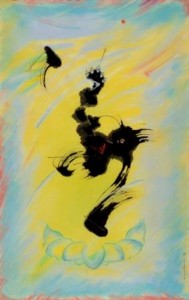

In the series that came to be known as Patent Leather Ladies, I explored and wrote about precision and grace through expressive large spontaneous brushstrokes of wisdom dakinis, or sky dancers. I only kept the brushstrokes that were true to tigse, which I measured after they dried. I was curious to see if the precision and grace of the specific proportions of a buddha figure had really seeped into my artistic anatomy. These immediate brushstrokes seemed like a viable, kinetic experiment to prove or disprove that question. In other sequences of painting I played with the magnetism and command of mudra gesture, the abundant display of mandala environment, and the pristine seeds of maitri practice. I wrote in my journals and, for non-Buddhist audiences, used visual presentations in unusual ways to accentuate lectures on the liberating symbolism inherent in Buddhist art.The earlier works I had begun in the mid 1990s such as the Maitri Seed Series, Turning the Wheel– a Travel Game, Patent Leather Ladies, and others, led to a new means of expression through group presentations and outdoor performances. In 2001, as I became a part of the faculty team for the master’s degree program in contemplative education, the practices I had done primarily in the privacy of my studios took on new dimensions. In a progression of classes that we named “Aesthetics,” I introduced students to working in ways that were dynamic, exploratory and steeped in developing presence and release on the spot. These brushstroke performance exercises, named “Indelible Presence Brush Practice” came forth quite readily with fresh variations continuing to this day.

In 2003, Acharya Dale Asrael kindly invited me to join her in the annual spring retreats she leads at Shambhala Mountain Center in the mountains of northern Colorado. Harbored within the context of a precise and inspired container, individual and group exercises with brush, ink and surface have become a part of the meditation retreat experience. These brush practices provide an expressive counterpart to the introspection of retreat and underscore the guidance and deep insight that Acharya Dale extends in her teaching, which naturally arises from her lifetime commitment to being “on the cushion.” I am deeply grateful to Dale for inviting me to be close with her in this way. We continue to inspire one another, she as the mirror and I as the brush, in a precious and unique experience with every retreat.

In the past year-and-a-half in which I have offered these practices to the Shambhala community and beyond, a weekend program has developed–“Envisioning Enlightened Appearance: the Art of Visualization and Vajrayana Buddhism.” Opening the three-day program, we first look at the historical development of the image of the Buddha figure. In the following two days we continue with traditional and contemporary exercises that help us to develop confidence in our visualization practice. Drawing aspects of the Buddha’s iconography through simple methods is effective in visualizing their forms. We work in solo and group arrangements coupled with talks and meditation practice. Full training in becoming a thangka painter is not necessary in order to gain benefit from the discipline of drawing the Buddha and in the release of animated gesture through brush stroke practice. Through guided group partnership and wide-open, preferably wild environments, all of the “Indelible Presence” creative practices are uniquely expressive within a contemplative perspective. Out of this impromptu alliance of fellow practitioners performing brushstroke simultaneously, the collective dedication and extension of merit from our activity glows preciously.