Thursday

Dharma TeachingsThe Protector Ritual

A long-time student ruminates on the practice of protector chants in Shambhala ritual

by Russell Rodgers

The protector chants have been causing controversy at centres since Trungpa Rinpoche first asked us to start doing them over thirty years ago. Periodically, members argue over whether or not it is appropriate to expose new people to them, fearing, perhaps, that the bloody imagery will frighten them off. Or, maybe, new people will develop resentful feelings that they are being asked to take on the religious baggage of Tibetan culture. Our own culture’s religious baggage seems to have reached dangerous proportions, and it’s certainly understandable that people would be sensitive.

The protector chants have been causing controversy at centres since Trungpa Rinpoche first asked us to start doing them over thirty years ago. Periodically, members argue over whether or not it is appropriate to expose new people to them, fearing, perhaps, that the bloody imagery will frighten them off. Or, maybe, new people will develop resentful feelings that they are being asked to take on the religious baggage of Tibetan culture. Our own culture’s religious baggage seems to have reached dangerous proportions, and it’s certainly understandable that people would be sensitive.

There’s no denying that there is a steep learning curve connected with the protector chants. My own feeling, having done them decades at this point, is of more and more appreciation for why Trungpa Rinpoche asked us to do them. I’d like to share some of my perceptions about the nature of these rituals, and, in future essays, talk about the specific contents of each chant. In this essay, I’d like to focus on how we use ritual in general to make our rigid personal realities more pliable.

When we perceive something, the first impression coming in from the senses is mere sound, mere sensation, or mere appearance. By “mere” we mean unadorned, nothing added. Sometimes in sitting practice we might have the very simple perception of our body as an outline in space. An itch might be mere sensation, not good or bad. To these first impressions we unconsciously add associations and names. Looking at the wall in front of us, we “name” it as a “wall.” From the past memories, we think it to be solid, so we don’t try to walk through it. We know it as a specific type of wall—drywall or brick or wood—each of those designations has countless more associations that are added to the mere image that just our eyes perceived. On top of all that are our feelings of like or dislike for the appearance of the wall. All of this is unconscious. If we saw the wall as mere image, it would be like the image in a dream when you recognize that you are dreaming: just an image that doesn’t dictate a particular way of behaving towards it. In a dream, you could walk through it if you wanted.

The result of this way of perceiving is that our world is rigid and stale. We are living in a world of past memories, learned associations, and concepts about things, rather than direct contact. In fact, some experiments have shown our associations are so powerful that if you don’t have concepts or associations for something, you won’t actually see it. There is, for instance, the story of people living in the jungle, who don’t have a concept of airplane, and so they don’t actually see the airplanes that regularly fly over their homeland. A major effect of our projections is that the world loses its fluidity and self-existing magic. We become prisoners of our own habits, and our world becomes stale and closes in on us.

We do rituals all the time, unconsciously. When we brush our teeth in the morning, is it actually the case that removing a thin layer of film from insensitive bone really makes us prepared for the day? We brush our hair, shave, put on deodorant, and then we think about our morning coffee. Even thinking the word “coffee” has an effect on us—we get a slight buzz. Our choice of clothes determines how we will go through the day. Through the rituals of apparel, we shape how others will relate to us.

When we shake hands, say “hello” or “how are you,” our mind rides out on the gesture and meets the mind of the other person. Our world expands a bit to allow the other person in, or at least relieve social tension. There are countless rituals connected with money, politeness, food, flirtation, who to make eye contact with on the street and so on. We continually use unconscious ritual to navigate our habitual world and make adjustments to it.

Certain kinds of ritual can function as a way of moving our frozen projections around and making the world more malleable. Conscious ritual, ritual that we are aware of as we do it, opens up psychological space beyond the ritual itself. It becomes more than just making us comfortable with the other person. Our awareness travels in the direction prescribed by the ritual, but its destination is wide open. When we are aware of ritual, we transcend it.

Buddhists call this state of mind “emptiness”. It is empty of projection or distortion. If you are completely there with your awareness when you shake hands, you are wide open, and anything could happen. Your connection to the other person could take you to Vienna, or Singapore.

In order to be effective, Buddhist ritual should be done consciously, with present awareness of all the parts of the ritual, and also awareness of the limits of the ritual itself. We know that the ritual or chant is a mental fabrication, our imagination, but we let it direct our awareness beyond the limits of habit into areas where our our awareness might not otherwise go.

Rituals like the protector chants take us beyond what we can do in simple sitting practice. As we sit, we as beginners usually only recognize the grosser, more obvious thoughts. The subtle associations and projections with which we fasten down our world are harder to spot and let go of. Vajrayana rituals like the protector chants point us back to the underlying fluidity, magic and sacredness of primordial existence.

The protectors, specifically, are connected with the karma principle. Karma means action, continual change and flux, the active principle of reality. This active principle is threatening to habitual pattern. It’s connected with impermanence and groundlessness. When we try to fight the karma principle by stopping change, we experience change as the pain of losing ground. Of course, karma also refers to karmic consequences: when you push something, it creates ripples of cause and effect. These could be positive from the point of view of our path, or our egos, or negative with respect to either. However, the more awake we are to change, the more even seemingly negative situations just become part of our path.

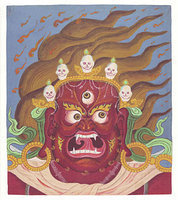

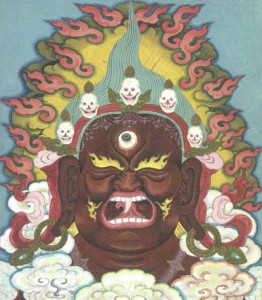

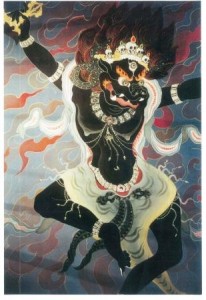

In order to create a ritual to evoke the karma principle, we need to have images to work with. The images in this case are uncompromising and blunt, like reality itself. The protectors are surrounded by flames, symbolizing tremendous energy and wrathful compassion. This compassion burns away projections that will ultimately cause us alienation and suffering. They wear garlands of human heads that represent thoughts and emotions that are self-liberated as soon as we recognize them. In some sense the protectors are more real than our habitual, protected world. They are more real, because they represent unvarnished reality itself.

The ritual of the protector chants points our awareness toward feedback from the world. We regard this feedback as the language or action of the protectors. We become sensitive to more and more subtle signals from the world. We become super-sensitive to karmic cause and effect.

Our relationship to the protectors can be summarized by a line from the Vetali chant, referring to her as our mother, sister and maid. At first, we don’t understand her principle, and the karmic feedback from the world seems capricious—unrelated to what we think we deserve. A child might feel this way about the actions of his or her mother. Later, we appreciate her as a sister. At this stage we are tuned into the kind of action and consequences that she symbolizes. We are sensitive to signals from the world. Vetali is a colleague. Finally, she acts as a maid. There is no separation from the flux of the universe. We are one with it, we appreciate it. It works for us. Because we are aware of it, we can use the active quality of the universe to help others.

Russell Rodgers has been wondering about this kind of topic for the 39 years that he has been practicing. He resides in the Kootenay mountains of British Columbia, in the town of Nelson, and has graciously agreed to allow publication of his beautiful essays on the Shambhala chants here in the Times.

Russell Rodgers has been wondering about this kind of topic for the 39 years that he has been practicing. He resides in the Kootenay mountains of British Columbia, in the town of Nelson, and has graciously agreed to allow publication of his beautiful essays on the Shambhala chants here in the Times.

Aug 19, 2016

Reply

I appreciate this article very much. Thank you.

Aug 19, 2016

Reply

Thank you for this essay! I have wondered about the protector chants & their relevance since first coming to Shambhala 9 years ago. But an early meditation instructor wisely advised “just do it & the wisdom will unpack in due time.” Today, some unpacking.

Aug 19, 2016

Reply

Thank you! Thank you!

Aug 18, 2016

Reply

In consideration of how much things have strayed afield since I entered the community in 1974

this is one practice I still feel connected to. Certainly sitting practice as shown by the Venerable

Chogyam Trungpa Rimpoche, more profound than most, it is not simple as it seems.

For whatever it is worth, nightly I toss the tea