Monday

Dharma TeachingsEkajati and the Ati Teachings

Exploring depth and meaning in the Ekajati protector chant

by Russell Rodgers

This chant has an extraordinary level of teaching in it about the nature of mind and the nature of reality. To the extent that one truly understands this chant, one will understand at least on a conceptual level a lot about the ati teachings and practices, the highest in the Nyingma lineage.

Ekajati is a protector of the ati teachings. The lineage of ati started in Tibet with Padmasambhava, in the 8th century CE. (In contrast, the Four Armed Mahakala, subject of an earlier essay is a protector in the Kagyu lineage, which started about 400 years later). Before he left Tibet, the Vidyadhara Trungpa Rinpoche was abbot of several Kagyu monasteries, but many of his main teachers were Nyingma, and they introduced him to the ati teachings. For this reason, both Kagyu and Nyingma lineages form the basis of what we practice now as Shambhala Buddhism. The Shambhala aspect of our lineage was also present in Tibet, but it was not regarded there as a separate lineage. While it was intimately related to the Buddhist lineages, it also drew from wisdom embedded in Tibetan secular society and the pre-buddhist Bon religion.

A basic characteristic of both the ati and the Shambhala traditions is that they often give profound instructions very early in a student’s path. In this way, they establish a basic view of enlightenment from the very start. For instance, students in Shambhala Training Level I are introduced to unconditional basic goodness, a profound and advanced concept, and the rest of the training develops and elaborates on that view.

An ati example of profound instruction at the beginning occurs in the refuge section of the Sadhana of Mahamudra, where one takes refuge in earth, water, fire and all the elements, manifesting as self-existing equanimity and the spontaneous wisdom of the trikaya. In other words, one takes refuge in reality, as an enlightened person would experience it. In contrast, a more Kagyu style of taking refuge would have us taking refuge in the Buddha, the dharma, and the sangha. If the trikaya seems a little abstract to you, the buddha, dharma and sangha are more easily accessible. You can actually picture them in your mind. It could be said that the Nyingma style is more direct and the Kagyu style is more easily understood by beginners like ourselves.

In Shambhala and in Ati, there is tremendous faith that people can recognize their basic nature. In the ati teachings, one might be given a view of primordial purity— that all phenomena are pure from the very start. Any apparent stain is only that: something added. Even stains themselves are pure in their nature if looked at in nowness and with complete awareness. This is very similar to the notion of basic goodness in Shambhala Training.

Advanced teachings demand protection to be effective. Shambhala Training is offered to anyone who signs up, but it is carried out in a highly structured and protected container. This container consists of numerous staff, an atmosphere enhanced with flower arrangements, and a certain degree of formality mixed with gentleness, relaxation, and dignity. The director takes his or her seat placed in front of the shrine, with a flower arrangement and a glass of water. The Shambhala container encourages respect and openness to the teaching that takes place.

Likewise, the ati teachings also require protection, symbolized here by Ekajati. In this case the container is our lives. She has various jobs to do, and we can recognize her actions by becoming familiar with the chant. If we recognize Ekajati’s activity in our lives, we will respect what she is protecting.

The chant begins with the syllable BHYO, by means of which we invoke her presence. Ekajati shares this syllable with other female protectors, such as Vetali.

The first paragraph of the chant establishes where Ekajati lives and what she represents. She arises from the suchness of penetrating primordial insight, and she is the all pervading essence of everything. She is the creator of samsara and nirvana. Therefore, we understand that Ekajati is an inherent aspect of our reality. With SAMAYA JAH we request the protectress to arise from space, and we invoke her vow to guard the teachings and practitioners.

The next paragraph can be a bit confusing, since it isn’t always clear from the words of the chant who is present and who is giving birth to whom. Here is an outline of what is happening, based on notes from the Nalanda Translation Committee: A very, very long time ago (before the first kalpa), the great lord and his consort united in mind without meeting. This refers to Samantabhadra and his consort Samantabhadri, who represent the masculine and feminine aspects of primordial buddha potential. These two are usually pictured as dark blue in color. They are naked, symbolizing the formlessness and simplicity of the dharmakaya.

The dharmakaya is related to the basic space-like nature of the mind, which is empty and at the same time holds the dynamic potential for anything to happen. Stabilizing the experiential recognition of dharmakaya in one’s own mind is enlightenment. For the Nyingma lineage, Samantabhadra and Samantabhadri hold a position similar to the primordial buddha of the Kagyu tradition, Vajradhara. They both represent the cosmic buddha potential from which earthly buddhas can arise.

Samantabhadri gives birth (from an iron mole on her forehead) to another form of herself, a wrathful emanation, Ekajati. Then the Lord of Secret, Vajrapani, who is also present, appoints her the protector of mantra. “Mantra” here refers to mantrayana, another name for vajrayana. Vajrapani is another deity whose function is to protect the vajrayana.

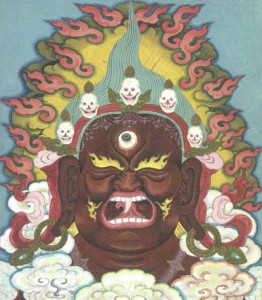

Ekajati has one turquoise lock of hair, one eye of dharmakaya on her forehead, one breast and one fang. These all symbolize the non-dual nature of the dharmakaya. In the dharmakaya, the split between self and other has not yet arisen, so there is just the one nature. She wears a cloud as raiment to indicate that she dwells in the expanse. She is surrounded by a retinue of a hundred thousand mamos. Mamos are wrathful goddesses, usually depicted as furious, ugly women. From a negative point of view, mamos cause all sorts of chaos in the world. From a positive point of view, they serve as reminders of awareness. For that reason some of them are highly regarded as protectors of the teachings.

Your single fang pierces the heart of Mara. There are actually four types of maras. The first is temptation to look at all the thoughts, feelings, and perceptions flowing through mind and to sloppily conceptualize these as a unitary self, giving them one label: “me.” The second mara is identification with one’s emotions as the truth about reality. The third is fear of groundlessness and death, which tempts one to over-react by trying to conceptually solidify oneself and the world. The fourth is seduction by pleasure: the tendency to want to dwell in only pleasurable situations and to ignore the rest. These are all pierced by the single fang of dharmakaya, which represents awareness and emptiness. In other words, their nature is exposed as empty in the same way that any thought held in full awareness becomes transparent.

Ekajati is both peaceful and wrathful. On the one hand the nature of the dharmakaya is inherently peaceful in its spacious simplicity and non-dual nature. On the other hand, when one tries to solidify the basic nature of reality with projections and the idea of a self, that very ultimate nature inevitably undercuts the smooth working of ego, sometimes abruptly. This is the function of a wrathful protector or a protectress.

Ekajati holds in her right hand a red heart ripped from a transgressor of samaya. Samaya refers to a promise made by tantric practitioners to respect the world as sacred and basically good. In the pure moment of awareness, what manifests on the spot has not yet been contaminated by dualistic concepts, good or bad. When a practitioner breaks this commitment to basic being, reality itself will intervene in the form of Ekajati.

In the chant we request Ekajati to manifest in various ways: as a torch of meditation, we ask her to illuminate the darkness of ignorance. When we are tormented by sloth, we ask her to be an arrow of awareness. When the practitioner is confused by doubt, we ask her to sound the trumpet of confidence. Sometimes the word “confidence” refers to the fact that the basic buddha mind, wakeful and empty yet expressive, is inherent in all experience. Thoughts, projections and perceptions change constantly, but the basic nature of reality does not. Therefore someone who is rooted in that basic nature will have unconditional confidence, even as superficial events are born from the basic mind and die back into it.

In the chant we request Ekajati to manifest in various ways: as a torch of meditation, we ask her to illuminate the darkness of ignorance. When we are tormented by sloth, we ask her to be an arrow of awareness. When the practitioner is confused by doubt, we ask her to sound the trumpet of confidence. Sometimes the word “confidence” refers to the fact that the basic buddha mind, wakeful and empty yet expressive, is inherent in all experience. Thoughts, projections and perceptions change constantly, but the basic nature of reality does not. Therefore someone who is rooted in that basic nature will have unconditional confidence, even as superficial events are born from the basic mind and die back into it.

“Cause the domain of the three jewels to prosper.” The three jewels are the Buddha (the premier example of human enlightenment possibility), the dharma (teachings), and the sangha, (the fellowship of those on the path). She also nurtures as her children the three sanghas: practitioners of hinayana, mahayana, and vajrayana schools of Buddhism.

We ask Ekajati to be especially wrathful with those who endanger the teachings. The chant lists three traps that can capture tantric practitioners. The tantras need to be transmitted in a proper way, at the right time when teacher and student are both open and available. At the wrong time, the words will be incorporated into and increase the student’s sense of self, and further distance the student from his or her own enlightenment. There is also a temptation to be arrogant–egotistically thinking that one is superior because one is a tantric practitioner. Finally, it is possible to pervert the teachings into the service of one’s ego. For instance, one might think that causing suffering in others to benefit oneself is all right since everything is sacred anyway. In this case “sacredness” has been reduced to a concept instead of a genuine experience on the spot.

In these cases, Ekajati’s action is to fiercely seize their hearts with venomous anguish, to kill them and lead them to dharmadhatu. Some people feel that this kind of activity is uncompassionate and unnecessarily violent. However in the second part of this sentence, having killed them, she leads them to dharmadhatu, or enlightenment. Dharmadhatu is a state which is even more empty and refined than dharmakaya. Perhaps one way of understanding these levels is by analogy to what happens to thoughts when they are brought to awareness (killed). Their insubstantial nature is recognized, and they fade back into the basic space of mind from which they came. For a mature practitioner, thoughts are thus an opportunity for enlightenment.

In the chant, there follow some praises to Ekajati. In the dharmakaya, she is self-liberated luminosity. Luminosity is the brilliance of appearance which arises within emptiness, and is inseparable from it. In the sambhogakaya, Ekajati is Vajrayogini. Vajrayogini is a deity who represents the communicative energy of the primordial dharmakaya. This energy manifests on the next level down, the sambhogakaya. On the level of the nirmanakaya, Ekajati is the mother of all. The nirmanakaya is the world that we experience with our ordinary senses. However, it is still infused with the emptiness of the dharmakaya, and the energy and communication of the sambhogakaya. The suchness quality of these kayas (bodies of enlightenment) is transmitted to ripened students by means of the fourth abhisheka or tantric initiation.

Next, in order to attract the energy of Ekajati, we make the outer, inner and secret offerings. Outer offerings are desirable objects of ordinary perception. The inner offering is one’s body. The secret offering is the offering of one’s emotions.

The chant concludes with a mantra in Sanskrit.

SAMAYA HO: This is an exhortation to keep the samaya, the promise to protect the teachings and practitioners.

OM MAMA RULU RULU HUM BHYO HUM: This is the mantra of a wrathful female protector.

MAHA-AMRITA-RAKTA-BALIM TE PUJA HOH DHARMADHATU EVAM: This could be roughly translated as “(Here is) an offering for you of great amrita, blood and food.” Amrita is a kind of blessed liquor that produces spiritual intoxication.

With these words, the chant comes to an end. We have invited feedback from the world. By regarding this feedback as the action of Ekajati, we take seriously its message to wake up to the world as path. The alternative is to feel that our world has once again victimized and insulted us. Which would you rather believe?

Feb 1, 2017

Reply

Thank you so much, Russell. We have a very special connection with Ekajati, and it’s illuminating to read your expansion of this very special chant.

Jan 7, 2017

Reply

Thank you for this series of articles on protectors and protector chants. I am really happy that you make these teachings available in this way, so accessible and clear.

Jan 7, 2017

Reply

Thank you so much. Very useful at this point. You offer hermano kind body and emoticonos.

Jan 4, 2017

Reply

Thank you so much.

Jan 2, 2017

Reply

Wonderful. Thank you Russell.

Jan 2, 2017

Reply

Heartfelt thanks, Russell, for the clarity of your exposition. and a good New Year.