Friday

Dharma TeachingsThe Joy Continues

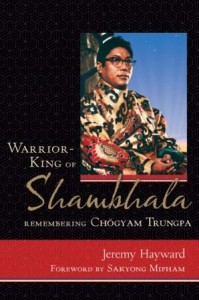

Excerpted from the book Warrior-King of Shambhala: Remembering Chogyam Trungpa by Jeremy Hayward

A Middle Way

If there is a middle way, even in regard to death, what might it be? To try to understand this, let us look at some ideas that Rinpoche himself conveyed to us about death. First, and in a sense foremost for all of us, is the fact that we are continually dying at every moment. As we saw in the discussion of the skandhas, our personality, our sense of me, as well as the world of appearances created by and for this me, is born and dies every fraction of a second. When we are afraid of death, or sorrowful about death, what is it that we fear or grieve for? Is it not largely our personality—me, my relationships, my life—that we fear to lose? From this point of view, then, death is happening all the time.

As Rinpoche taught, following the Buddha himself, death is in life, and whatever is born must die; impermanence is the nature of all created things. We know superficially, conceptually, that every one of us, including me, will die. But, at a deeper level, I don’t believe it of my self. The only epitaph on French painter Marcel Duchamp’s gravestone is: “It always happens to others.” And that is what we believe deeply, and what is the basis of almost all our actions . . . that I, the precious me myself, will last forever. Yet, the Buddha said, in the Sutra of Buddha Teaching the Seven Daughters, “If one knows that what is born will end in death, then there will be love.” The delusion of permanence-believing that we and others will go on forever, so that there is always time later for communication and forgiveness-hardens our heart and encourages selfishness, while the continual remembering of impermanence brings a sense of sadness, tenderness and love. And Gurdjieff too, when asked if there is any hope for humanity, gripped in the insanity of wars and mutual destruction, commented that only one thing could now save mankind from the madness out of which we destroy each other and our world. The only thing that could save us from this sleep is if a new organ could be planted in each of us that would cause each one of us, always and everywhere, to remember the certainty of our own death.

With this as the basis of our understanding, Rinpoche also gave clues that, in another sense also, death is no different from life. He was no more a nihilist than he was an eternalist, and clearly it was not his view that everything ends at death. What happens to us after death, he taught, is a continuation in a different form of the habitual patterns of our life. Death is happening at every moment, thereby bringing continual discontinuity to our lives. The big Death is simply another instance of this . . . the “great discontinuity,” or “the continuity of discontinuity,” as Rinpoche himself called it.

He had said to me, as the plane landed in Denver back in 1974, “If we crash I’ll see you in the bardo”; and in response to my question of how I would find him he had said “Don’t worry, I’ll find you.” I now believe that he meant this actually, not only for myself but for all his students who have sincere and deep devotion to him, whether they met him in his body or not; he can be there, if we remember him, to guide us through the journey of mind through the bardo. Likewise, in his final few years he had started the strange practice of singing the Shambhala Anthem in a high screeching falsetto, usually accompanied by one or two ladies. It was both weird, hilarious and somehow moving to see his enjoyment. When asked on one occasion why he did it, he replied, “So that my students can find me in the bardo.”

The Joy Continues

In 1982, Rinpoche had given a public talk on “Creating an Enlightened Society,” which took place in front of hundreds of people in a grand old church in Boston. During the question and answer period, this exchange occurred between Rinpoche and a newcomer:

Questioner: . . . is there a way to understand better what it means to love someone and have that person die and to know that a lot of people are going to die throughout one’s life? Is there a way to understand that?

R:… Well, I think the basic point here is that death means another sense of a living situation. It’s kind of life in a different planet, a different realization. Reality of death shouldn’t be cultivated, and the realities of life shouldn’t be cultivated . . . saying that once your life is out then you are off altogether. So one should maintain some sense of loyalty in a situation of death. I think some sense of joy is always. . . . Joy doesn’t depend on life or death . . . never . . . never . . . never. Joy is always joy. Joy doesn’t depend on a smile alone. Joy depends on the brilliantness of light [luminosity], always, whether you live or die. So I think you could let people who are dying [know that] that kind of joy of living brilliantness, which is a smile . . . always happens. And that brings a sense of cheerfulness. In the Shambhalian language we talk about seeing the Great Eastern Sun eternally. . . . So joy always comes.

Q: So are you saying that joy remains regardless of the fact that there is death.

R: That’s right, not joy of this and that. But just purely joy without the “of.” Just joy. Joy and space, as Great Eastern Sun shines.

In speaking of the continuity as a “kind of life in a different planet,” Rinpoche is, perhaps, referring to the view that the karmic patterns, which we have created through our ego-centered actions in this life, do continue; that is, our actions in this life in some way sow seeds in the cosmic realm which come to fruition in future lives. Cause and effect go on. And in speaking of the joy that remains, “which is a smile,” he seems to be once again referring to that luminosity and humor which has been one of the themes of this story.

Rinpoche wrote in his will, “I take my joy along with me”, telling us, in other words, that he too would continue with joy. He also gave us many clues regarding the living continuity of our connection with him, beyond merely dwelling on memory alone. For example, at the 1976 Seminary, this exchange occurred between him and a vajrayana student :

Q: What happens if the guru dies before the students finish [the path]?

R: Well, the students should continue. There is no choice. When your schoolmaster dies, you don’t therefore just run around the world. . . . You go back to school.

Q: Oh, so you wouldn’t work with another teacher?

R: Not necessarily. There is also glowing warmth somewhere in the neighborhood.

In the Farewell Address at the end of the 1979 Seminary, he said about his own long-deceased guru, Jamgon Kongtrül:

I am planning to let his Holiness Karmapa know what we are doing, so that his life will be prolonged. I am planning to tell Khyentse Rinpoche too, as well as my teacher, Jamgon Kongtrül, who is always here—and I am sure he will be very pleased. My only regret is that I wish he could be here in his physical body so that I could introduce all of you to him. That has somewhat taken place, but somewhat it is uncertain.

At the inner level, Rinpoche emphasized again and again that the dralas exist as much as we do. He said, as I quoted previously, “Why on earth do you have to create a barrier to exclude the dralas from your life? They are longing to meet you.” Rinpoche concluded the draft of his will, written during his Mill Village retreat: Altogether we are happy to die. We take our joy along with us. It is unusually romantic to die

Born a monk

Died a king—

Such thunderstorm does not stop

We will be haunting you along with the dralas.

Jolly good luck!

And another poem, Death or Life, written in July, 1985, expresses a similar commitment:

Death or life:

I still grind the sun and moon.

Whether your kingdom is established or not,

I will be the ghost that will manifest Tiger and Garuda

Whether it is a joke or serious business

I will hang around as a ghost or anger

Until you succeed in accomplishing the Kingdom of Shambhala.

Joy for you.

Nonetheless, powerful haunting cloud should hover

in your household and on your head:

The Dorje Dradul as misty clouds or brilliant sun.

I will be with you until you establish your

kingdom.

It seems, then, that he left many clues that he believed he would continue to be present for us, after his physical death, “along with the dralas.” He spoke of King Gesar, the progenitor of the Mukpo clan and king of medieval Tibet who unified warring tribes and brought peace throughout Tibet, as an “ancestral drala.” And Rinpoche implied that a human being can become a drala when he wrote:

Finally, the wisdom of the ultimate and inner drala can be transmitted to a living human being. In other words, by realizing completely the cosmic mirror principle of unconditionality and by invoking that principle utterly in the brilliant perception of reality, a human being can become a living drala—living magic. That is how one joins the lineage of Shambhala warriors and becomes a master warrior—not just by invoking but by embodying drala.

Change Continues

As we contemplate these things, it may begin to seem clear that Rinpoche was letting us know that he would, indeed, somehow “hang around” as the closest ancestral drala of the Shambhala lineage, and the main link with the drala realm for anyone who cared to open to that lineage.

Rinpoche’s death, then, seems far from the end of the voyage, either for those who knew him in his dear, lame body, or for those who did not have that fortune, good or bad. Rather, it looks more like an invitation to a fresh direction, as he so often invited us in his life on earth. The sense that the mind of Rinpoche is in some way still available to those who are open to it is very strong. Many people who never met Rinpoche have been brought to the dharma through vivid dreams of him, or through feeling a deep and immediate connection with him on reading his books, and this has continued after his death. Rinpoche’s presence is felt, especially, in Shambhala Centers in which the environment is so much a reflection of his mind. He put tremendous energy and care into creating environments during his life, environments that are created by an awake mind and are able to transmit that wakefulness to present and future generations.

The tremendous force of his seventeen-year presence in the West continues, perhaps even more strongly, as the years go by. Seeds that he sowed are still sprouting and growing; some, such as Naropa University are shining in the full bloom of youth; others are kept alive, but barely, by their stalwart guardians, such as the Mudra Theatre group, the Upaya Council for dispute mediation, the Ashoka Credit Union, conceived to be eventually an independent banking system, and many other projects which I have not had the space to mention.

Thirty years after Rinpoche’s first proclamation of the vision of Shambhala, it is most extraordinary to realize how much has been done in Nova Scotia to join the vision of Shambhala with the goodness of the local culture. Many Shambhalians, local Nova Scotians as well as many “from away,” have established families in Nova Scotia, set up businesses, consulting services, and organic farms, founded a Shambhala-based school, organized environmental agencies, and generally entered into the life, culture, and business of the province. The Shambhala Buddhists are well known in the province and there is a great deal of mutual respect and interchange between the two cultures to the benefit of both. In 1998, the Premier of Nova Scotia was invited to speak at the annual meeting of the Board of Directors of Shambhala. He was unable to attend as a Conference of Canadian Premiers had been scheduled at the same time. However the letter he sent to the Chair of the Board included the following paragraph:

I want to express my appreciation for the contribution the Shambhala/Buddhist community has made to Nova Scotia. The community has brought much to the province over the past decade. Nova Scotians appreciate both the innovative contributions of many individuals in the fields of health, education, the arts, business, and the social services, as well as the confidence the Shambhala group displays in Nova Scotia as a place where a dynamic future founded on basic human goodness can be created.

Some Seeds Have Begun to Blossom

It took many years for the seeds that Rinpoche had sown in us to blossom, or at least to show tender shoots in myself and others. Yet, to try to put into words the outcome of this voyage of practice and devotion is like trying to see a comet in the night sky. I recall one occasion when a famous comet had been around for a few days and my father came to me excitedly one evening saying, “Let’s go and see the comet.” We drove out to a hill and looked up—the comet was supposed to be near Cassiopeia—but we found that the only way we could see it was to not look directly at it. Try to grasp ones experience in words and it slips away, try to say what one has discovered and one wonders . . .

And the idea of getting something out of the practice of meditation is not the point, of course, as Rinpoche emphasized over and over again. It comes back to hopelessness, not in the sense of depression or despair, but in the sense of genuinely giving up the hope of getting anything out of meditation or out of anything else. As Rinpoche again emphasized over and over, the point is that we already have all we need, and I believe I am beginning to realize this at last. And so, as the years have gone by, I have begun to give up hope—at least a little. The hard shell of arrogantly feeling I am or should be, or should at least pretend to be, someone special has begun to drop away (if my friends would permit me to say so!) and I can, quite joyfully, feel a little more humble. I know, more genuinely now, that I am really just a beginner. But when you enjoy the path, as the Dalai Lama says, “It’s good to know you are just beginning, because then you have a lot more of the path to enjoy!”

Perhaps this conclusion of the quote from Lodro Sangmo (on Rinpoche’s goal for more male/female balance on the Board, in Chapter 10) can give some idea of the kind of change that came about in myself, as well as in many others:

My hope for anyone who does not have the experience of being seen completely, heard completely, and loved completely, is that you have that even for a moment in this lifetime. For if you do, you will understand better how deep this need is in us. Is it the powerful brilliance of our own nature longing to break out? You will understand better the heart-bursting appreciation many of us still feel for this long-dead Tibetan with the warm smile. And the quite remarkable transformation of even the once-stuffy, always brilliant Jeremy, that I have witnessed, would make sense to you. Somehow being on this path for all these years, and the utter love Jeremy feels for his teacher, has softened his edges, taken the prickles off the rose, so he has not become different but who he always was inside—now visible and out in the open for all of us to enjoy.

I too saw such softening and opening among many of my friends and colleagues; and, as well, I saw a growing strength and joy. I have seen many of Rinpoche’s students change in this way almost miraculously. Yet, as Lodro Sangmo says, they are not different from who they always were. It is as if at last we are able simply to be who we always were, without constantly wanting to be something else—better or greater or whatever it may be.

There have been fellow students who for many years I could barely stand to be with for ten minutes. Even though I knew they were good people and struggling on the path just as I was, their rough edges whether of angry self-righteousness or seductive “come-hither” were just too unpleasant to be around, at least in my perception. Then, years later, suddenly I would see them again—just the same person, yet those same characteristics that had seemed so unpleasant to me had subtly changed, as no doubt had I. The inner core of “look at me” seemed to have dissolved a little and there was genuine communication and even affection between us. As dear friend Jerry Grannelli once said at a recent occasion when many of us were together again for the first time in many many years, “The definition of Buddhist Alzheimer’s is that you can’t remember why you hated someone!”

Through the voyage of being with Rinpoche and following the path of practice and understanding he laid out, I have been shown a previously unrecognized capacity for love and friendliness towards both myself and others. Along with this is the power of windhorse—to be able to rouse a sense of cheerfulness, presence, and humor whenever I begin to feel myself slipping and sliding once more into that black hole. Raising my own life energy of windhorse enables me to feel less separate from the energy and vividness of the world around me, and this in turn brings appreciation and the aspiration to make whatever small effort I can to help others. To gradually learn to appreciate and feel the reality of dralas—the personal drala of windhorse, the dralas of the elemental and subtle energies of the world, and potency and humor of the ancestral dralas of Shambhala—has been a continuous adventure.

And, as perhaps the source of all of this, I was gradually able to overcome the nihilism of my scientific upbringing. I learned to trust, at a level far deeper than mere conceptual understanding, that the cosmos is so much vaster, richer, and more multilayered than is dreamed of in the minds of materialists and so-called “realists.” I have seen through the mistaken philosophy—though truly religion might be a better term—of scientific materialism and the deep conditioning that I, along with all others brought up in the modern educational system, were subjected to as children when we were too young to question. This has brought the possibility of opening, however briefly, to luminosity beyond thought; sensing/feeling, as if through a glass darkly, the light that is neither inner nor outer but is the natural radiance of all that appears.

These gentle, but vivid hints of “what is left” perhaps are made possible also from the intense contemplation during all those years of what I gradually came to see as the essential message of both the Buddhist and Shambhala teachings: that in our normal ways of living there is a disparity between appearance and reality; and it is this that brings our deep anxiety and fear. Through practice and study appearance and reality can gradually be brought together and when they coincide, even for a moment, that is the realization of emptiness and joy. As it is said of the great bodhisattvas, in the Heart Sutra, “Since there is no obscuration of mind, there is no fear. They transcend falsity and attain complete nirvana [realization of emptiness/luminosity]”

In this contemplation, the question then becomes: what are appearances and what is reality? What is the process of perception that gives rise to appearances, and what is the reality from which those appearances arise? And here we are back to the old issue of the view of perception in Buddhism and cognitive science, which I have already discussed. Over the years, I contemplated these things, especially the extraordinary agreement between Buddhism and cognitive science that what we think we are experiencing as an outside “real” world is in fact 99.99% the creation of our brain/heart/mind. And at the same time I was examining directly the nature of perception through the meditative practices that Rinpoche had given us. Then gradually I began to feel at a deeper level than mere thought that there truly may be nothing substantial behind the appearances. Touching this discovery brings a sense of relief and freshness, and the ironical humor that was Rinpoche’s hallmark until his last breath. At those moments the world really does appear like a mad dream, yet that dream-like appearance seems closer to the truth of how things are than when I take my world to be real.

In the end, the sitting practice of mindfulness and awareness seems to be the foundation of all of this—simply sitting, letting go. Of what? Of everything. The joy of sitting practice, which I felt at the very beginning of my voyage, has been the thread (sometimes a very thin thread) through all of this. Even now, it is far easier said than done. Nevertheless, by just sitting without expectation, the natural stability and clarity of my mind gradually strengthens, little by little. Then I am able to turn that mind upon itself and inquire, “Who? What? Where is that mind?” Not finding anything brings further giving up and a little bit of relaxation in genuineness. With this comes a small further step in understanding the truths of basic goodness, the cocoon by which I cover that, and the way out of the cocoon to realize that basic goodness, our inherent nature of wisdom.

It can be tremendously inspiring and uplifting to look back over our lives and to realize that we have, after all, gained some understanding of these precious and noble truths. And the most important thing seems to be to try to remember to bring that stable, clear and inquiring mind into daily activity, at the same time as being in the activity—to continue that openness expressed in my very first question, “What?” The most important practice of all seems to be to remember, remember, remember . . . at each moment of the day.

My greatest longing is that I might be able to pass on to others even a small spark of the love and insight that I received through the years with Rinpoche. The vision of an enlightened society, putting my energy toward helping the world in whatever small way I can, is what makes it all worthwhile. It is important to try to help alleviate the tremendous physical and psychological suffering in our world. But, sadly, much of this work is reactive—putting patches, absolutely necessary patches, no doubt—on the situation while not fundamentally changing anything.

I believe that Rinpoche’s primary teaching was that the only way to genuinely help the world is to help others to see the cause of that suffering—belief in personal or national ego—and the possibility of being liberated from that suffering through realization of egolessness, basic goodness. As James George writes in his book, Asking for the Earth, “To solve the ecological crisis, we must resolve the spiritual crisis too; and I think there can be no doubt that it is the spiritual crisis that will have to be solved first, for only when we have begun the inner transformation towards which the spiritual crisis is leading us will we be able to change our outer behavior on a scale that will permit the earth to recover.” This view can be extended beyond the ecological crisis to all the man-made crises of famine, the appearance of diseases previously unknown, and warfare with weapons that could destroy most of life on earth.

As the years have gone by, my relationship to Rinpoche has constantly changed. Love for Rinpoche, and the joy that goes with that, has grown clearer and deeper, less obstructed by all the remorse about what I did or didn’t do or say, all the clever questions I didn’t ask. At the same time, the longing and heart-rending sadness at being separate from him also only deepens. So the journey with Rinpoche seems to go on and on . . . Perhaps it will go on until I finally realize my own inseparability from that wisdom. Once, in the early days of tantra group meetings, there were many of us crowded into Rinpoche’s room, asking him about the meaning of the vajrayana transmission on the nature of mind—”Is it like this, Rinpoche?” “Is it like that, Rinpoche?” This went on for some time while Rinpoche sat in a corner, rather darkly just saying, “No.” After a while I said, “Rinpoche, you seem to be disappointed in us.” To which he replied, “I will be disappointed in you until you attain enlightenment.” That was good news—he would actually stick with us until we attained enlightenment, which might be a very long time!

My aspiration for readers and author alike is that the conviction may grow in us in the truth of this verse from the Mahayanasutralankara by Asanga, which seems to summarize the whole inconceivable voyage:

After the awareness that there is nothing other than mind,

Comes the understanding that mind, too, is nothing itself.

The intelligent know that these two understandings are not things,

And, not even holding onto this knowledge, they come to rest in the realm of totality.

( c ) Jeremy Hayward, 2007. Reprinted from /Warrior King of Shambhala: Remembering Chogyam Trungpa/, with permission from Wisdom Publications, 199 Elm Street, Somerville, MA 02144 USA. Wisdompubs.org

( c ) Jeremy Hayward, 2007. Reprinted from /Warrior King of Shambhala: Remembering Chogyam Trungpa/, with permission from Wisdom Publications, 199 Elm Street, Somerville, MA 02144 USA. Wisdompubs.org

Click here to purchase a copy

Apr 14, 2009

Reply

Thank you Jeremy! Thank you for remembering and for igniting our remembering! Thank you for rekindling our devotion!

With love

S