Monday

Dharma TeachingsWhen Monsters Become Protectors

The Transformational Power of Storytelling

By Laura Simms

Shortly after 9/11, I was asked to tell stories to children at several public schools in downtown Manhattan. My task was to generate conversations with children about what they had experienced and what fears were lingering. I went to PS19 on the lower east side to talk to a group of fifth graders. I chose to begin by telling the Norwegian tale of The Giant With No Heart. It is a fairytale about a giant whose heart was hidden on an island, in a tower, in a well, in a duck, in an egg. At the end of the story a youngest prince of six brothers — a kind of fool hero who showed kindness to a raven, a fish, and a starving wolf — retrieved the heart and freed a princess who was held captive by the giant. In the traditional version, the prince destroys the heart and the giant dies. Then the prince married the princess and everybody lived happily and safely ever after.

That day at PS19, when I said, “…and the prince destroyed the heart and the giant died,” a boy leapt out of his seat in the auditorium and yelled, “We should kill every single person in Afghanistan!” This was a fifth grader. Instead of responding to his reaction I said, “There is another ending to the story.” Everybody’s ears were perked so I continued. “I don’t know how he did it, but you can do so many things in a story. The prince took the heart and put it back in the giant. The giant began to shake and to cry and he set the princess free! The youngest prince did marry the youngest princess, and the giant became the protector of the kingdom and the natural world.” Everyone seeemd satisfied. I added, “You can choose which ending you want.”

After that day, I told the giant story two or three times a day, in different schools in downtown Manhattan. The story navigates a wonderful journey that always engages young people of all ages. But what seemed to capture students the most was the new ending and the possibility of transforming heartlessness, evil, negativity, violence, and control over the feminine. I was inspired by the wrathful deities of Tibetan iconography, and by the truth of Basic Goodness. I learned long ago that as my audiences listen, drawn into the unfolding story, bringing it alive in their own minds, there is a natural opening or melting of their minds and the presence of inherent goodness arising. For that period of time, the principles of protector and basic goodness seemed like essential medicine.Since then, I have been creating activities that use this idea of transforming negativity into compassion, of changing aggression into actions that bring benefit. After the story telling, my audience engages in writing exercises in which they invent a monster who has a supernatural generic power that can be used to destroy and can also be used to bring relief or immense kindness. Through this creative process, intense confusion, ignorance, and aggression become visceral wakefulness. I trust that what is uncovered and felt by my audience is basic goodness.

One of the strongest motivations for deepening my understanding of how transformation can work is my experience with my adopted son, Ishmael Beah. His life story is an example — like the story of Milarepa — of someone who, as a child soldier in Sierra Leone, participated in devastatingly violent and unimaginable activities. By accessing his own bodhichitta, the living joy of basic goodness that never faded, he was able to make use of his life story and turn it into a mission to benefit other people. He is a wholly cheerful person. [Editor’s note: Ishmael Beah is the author of the bestselling book A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, www.alongwaygone.com ]

This past winter an interesting thing happened while I was working for a performance company outside Vienna called Cabula6. We were working in an walled community that had been a Nazi barrack. The area is now a place for prisons, garbage dumps, cemeteries, and immigrants. Macondo, as it was named by dissidents from Chile who have lived there for the past thirty years, is a step up from a refugee camp. The building where I worked was called “The Transitional Place.” On paper, refugees are to live there from three to five years. But in reality, many people have been there for thirty-five years; immigrants from Vietnam, Chile, Hungary, Turkey, Africa and more recently Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq and Chechnya. It was neither a stable community nor a refugee camp. There were many different cultures living side by side in small three-storied barrack buildings. Each had different backgrounds and ethnic or gender issues. Because some people worked and others traveled daily searching for work, no organizational structure was in place in the community. My situation was challenging.

I put a hand-written sign on the glass door of a building. In the late afternoons, I waited for children to arrive. Different children came, and after a few days several of the same children found their way to the basement room. Seven kids returned again and again. They were wild — particularly the kids from Chechnya. I was later told that they had never lived in peace in their entire lives. Unlike the Iranian, Afghan, and Somali youth I worked with — who wanted to build new lives – the Chechen families were waiting for a moment of peace so they could get back to Chechnya and finish the war. As a result, the children seemed restless and aggressive.

During the six days, I tried the same monster exercises I had introduced in Manhattan. The director and I began with physical, repetitive activities, hoping we could use up some of their energy and help them to focus. After fifteen minutes, it was evident that the only ones becoming worn out were the director and myself: the children were tireless. We set aside orange mats where I would tell stories with the translator sitting right up against me, as though I had a second mouth. That way, the children could look at me, but hear her translation. I began telling The Giant With No Heart, adding gestures and inventing tiny chants in German to involve them as best I could. Part of my goal was to get them engaged, focusing their attention on imagining, and give them some respite from the stress they seemed to be acting out. In some ways, it was a trick to help them discover that they had control over their bodies. They didn’t have to run around being rebellious all the time. They had tremendous energy and rather than suppressing it, we wanted to gather and focus it so they could listen, make stories and pictures, and learn to communicate with each other.

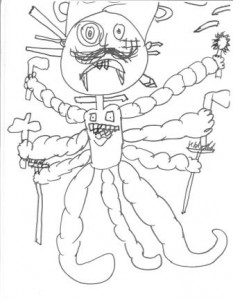

When the giant appeared in the story, and the children began inventing him in their imaginations, they were wide-eyed and pinned to their cushions. Whenever he showed up, their eyes grew enormous. Something was happening. They leaned in further, listening. and there was a general sense of settling down. I had no idea what images arose in their minds, but the intensity of presence was palpable. When we finished the story, I invited them to draw something from the story. I passed out paper and crayons. Except for one girl, they all wanted to draw the giant. The Chechen boys chose thick black magic markers. One of them began to draw with such intensity that the other boys basically copied what he was drawing. His picture was astonishing: a six-armed bowlegged giant with bulging muscles, intestines tightly spiraled in his square-shaped belly, wearing a metal hat like a pot, and wielding various weapons. I was immediately struck by how similar his drawing was to the Mahakala in our shine rooms.The next day when the children came back, rather than running around the room, the boy who had drawn the picture of the many-armed giant, whose name is Adam, asked me to tell another giant story. I went through my mental file and told a story about another giant: an Afghan folktale. Every afternoon for six days, I told a different story, with a different ending, and a different kind of confrontation with a monster, or a giant. In traditional cultures, stories end with the destruction of the negative energy because there is always another story. But at The Transitional Place, kids weren’t hearing traditional stories because war interrupts everything. And they have lived through events far more devastating than the violence in fairytales. So, as I do when there is really difficult character, I gave several endings so that the children could visualize and live through different possibilities, exploring many possible life maps. And after each story, the Chechen boy sat on the floor and drew a version of the same illustration with his thick black magic markers.

When the program was ending, I invited all of the kids who had come six nights in a row to gather and think about how we might clear a space for them in the grassless garden behind the Transitional House. I hoped they would envision what they wanted in that place. While many of them came back, the Chechen boy didn’t return which was sad because I liked him very much.

The kids got busy designing the ultimate playground, including underground areas where their monsters could live. Some had chosen monsters that were protectors, and some had wicked ones lurking around. The children imagined gardens where they would be safe and drew remarkable pictures of them, particularly the Afghan boys who framed their drawings with colorful birds, flowers, and Afghan flags. Just as we were changing gears and getting ready to put out food, Adam came running into the room, straight into my arms. We embraced. But within seconds, he showed the worst of his mischievous behavior by turning off the light, throwing full juice cans on the floor, and then attacking two other kids. For the first time at The Transitional Place, I felt it was my job to protect the children. I stopped him. I said in German, “Adam, you have to stop now. I want you to leave because you are hurting people. I like very much — I love your energy, but you are hurting people and you have to go!” He didn’t believe me and crossed his arms in defiance. I said to everyone, “Nobody can do anything until Adam goes.” He finally left, turning off the light again and then lingering at the door. I said to him, “If you decide you want to come back, come back, but you have to leave your anger outside. Then knock on the door three times.”

The kids got busy designing the ultimate playground, including underground areas where their monsters could live. Some had chosen monsters that were protectors, and some had wicked ones lurking around. The children imagined gardens where they would be safe and drew remarkable pictures of them, particularly the Afghan boys who framed their drawings with colorful birds, flowers, and Afghan flags. Just as we were changing gears and getting ready to put out food, Adam came running into the room, straight into my arms. We embraced. But within seconds, he showed the worst of his mischievous behavior by turning off the light, throwing full juice cans on the floor, and then attacking two other kids. For the first time at The Transitional Place, I felt it was my job to protect the children. I stopped him. I said in German, “Adam, you have to stop now. I want you to leave because you are hurting people. I like very much — I love your energy, but you are hurting people and you have to go!” He didn’t believe me and crossed his arms in defiance. I said to everyone, “Nobody can do anything until Adam goes.” He finally left, turning off the light again and then lingering at the door. I said to him, “If you decide you want to come back, come back, but you have to leave your anger outside. Then knock on the door three times.”

We were all sitting on the floor eating, when Adam knocked three times. I opened the door, and he said he wanted to come back. I said, “You can come back. You are welcome and I don’t want to take your anger away. But please go across the hallway and leave your anger by the elevator. Then come back. You can pick it up again on your way out.” He started walking toward the elevator. Then he turned around and called back “I can talk to it?” I told him he could. He gave me a funny look and said, “Okay.” I was distracted by something for a moment, and when I looked back, I saw him across the hallway in a wild mime dance. He was wrestling with the air and talking. Then, he put his hands up in front of him, in a classic gesture of “Okay stop, see ‘ya later buddy!” He came inside the room and told me in a whisper that he had left his anger outside. I invited him in to join us. His behavior was perfect.

My encounter with the Adam fascinated me. Instead of feeding his idea of himself as a bad boy, I hope he left with the sense that when his anger rose up again, it wouldn’t be the only part of him that existed. He might recognize that he could get some distance and actually negotiate with his temper without losing its’ immense power and energy. I wish I could have spent a longer time with Adam — his creativity and power could make him a generous leader.

Click here for Part 2 of When Monsters Become Protectors

Aug 31, 2009

Reply

Thank you, Laura, for sharing this story. It’s heart wrenching and inspiring. And hopeful and honest.