Sunday

UncategorizedBook Review: Training in Tenderness

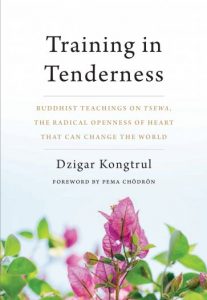

Training in Tenderness: Buddhist Teachings on Tsewa, The Radical Openness of Heart That Can Change the World

By Dzigar Kongtrul

Reviewed by Christine Heming

“Just give me some tenderness beneath your honesty.” – Paul Simon

Some weeks ago, I listened to the testimony of Mr. Michael Cohen before the US House of Representatives Oversight Committee. Some members of that committee chose to use their allotted time to verbally pummel Mr. Cohen, angrily reciting the litany of all of his offenses and dismissing him as unworthy of their time and interest. Among other things, this was political posturing, but it is not uncommon behaviour these days in which things are either one side or another – divisive, polarized, dehumanizing, and lacking heart.

How timely to have this teaching on tsewa from Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche. These teachings are not new, but it seems particularly relevant at this time to be reminded of this jewel that exists in our hearts and be encouraged to reflect on its power to heal our suffering and nourish our well being. And this is Kongtrul Rinpoche’s purpose. He writes, “I would like to make a clear case for the tremendous benefits of tsewa and the importance of keeping your heart open . . .tsewa is the most valuable resource human beings possess [and] I hope to help you remove whatever impediments are keeping it hidden in darkness so you can live a life full of joy, meaning, and profound value to the world.”

Kongtrul Rinpoche teaches that tsewa is like a seed, then like the water that nourishes the seed, until finally the seed grows into ripe fruit. These three metaphors come from Chandrakirti’s Introduction to the Middle Way. Rinpoche tells us that this rigorous treatise on the ultimate nature of reality begins with paying homage to tsewa, the tender heart. Without a tender heart, there can be no progress on the spiritual path.

Rinpoche gives us many suggestions for how to recognize and cultivate that seed of tsewa within us – for example, to think about a sentient being in a painful situation, such as an animal about to be slaughtered. Although there is nothing we can do about that situation, we can recognize the concern we feel. We can ponder again and again the suffering of other beings, strengthening our soft spot of tenderness, and recognizing that we are all vulnerable, that all beings suffer. It is tsewa that is the basis for all positive qualities. It is the generative force that has enabled us to survive. Kongtrul Rinpoche encourages us to observe how it feels when our heart hardens and closes down, and when it is soft and open. In this way, we will acquire the “taste” of tsewa and choose to let it flow.

But we are not always able to keep our hearts open, hence the need for training and reflection, the need to water that seed within us, the need to realize how significant tsewa is to our well being and the well being of others. This is where intention comes in. Rinpoche writes: “. . . to nurture the seed of tsewa, our own intention has to be involved. . . [and] it has to be imbued with wisdom.” This wisdom comes from applying our innate critical intelligence to discern the “unsurpassable value of tsewa.” We have to observe our heart over and over again, investigate the teachings and our experience, and then arrive at this clear and noble intention.

Sometimes when we examine our mind and we see how much conflict and confusion is there, it may seem impossible to open our heart. We experience what Kongtrul Rinpoche calls, “a mind in crisis.” We have many unhealthy mental habits; we let our mind become disturbed. He writes, “A disturbed mind is a poor atmosphere for tsewa.” At the same time, he reminds us that the human mind is endowed with two great protectors – mindfulness and vigilant introspection. Mindfulness enables us to know what is going on in our mind and heart; vigilant introspection means knowing how much is at stake, connecting the dots between cause and effect. Every moment we have a choice: perpetuate the story lines full of conflict, resentment, and self-righteousness or open our hearts with tenderness to others.

In one chapter Kongtrul Rinpoche addresses how to open the “injured heart” – the heart that’s holding a grudge. He acknowledges that when someone has caused you pain, it is challenging to keep your heart open to that person. But he cautions that a grudge against one person can turn into a much bigger form such as prejudice toward an entire group of people. He writes, “If you shut down your heart because of past injuries, life becomes a painful ordeal.” Anytime you think of the person or persons who hurt you, you will experience that pain.

Although it may take effort, we can let go and reconnect with the flow of love in our heart. Again Rinpoche teaches the necessity of being observant, noticing how we perpetuate the past, repeating the whole story to ourselves over and over. In so doing we are repeatedly harming ourselves and as well, our negativity can begin to affect those around us. Rinpoche acknowledges that some grudges may seem almost impossible to let go. He writes: “Whoever these individuals are and whatever they did, we have to keep in mind the bigger picture of what’s at stake: our wish-fulfilling jewel of tsewa. We need to be motivated and see that there is no good alternative except to soften and open our heart.

To help us have this motivation, Kongtrul Rinpoche offers ways we can put our story in a bigger context such as recognizing that all sentient beings wish to be happy and free of suffering, and that all the differences in how we appear and how we behave come from temporary causes and conditions, many of which are beyond are control. This is the limitless play of interdependence. He writes, “No one is permanently one way or another – good or bad, right or wrong, for us or against us.” When we view others through the lens of resentment, they seem to be permanent enemies. Rinpoche offers questions for contemplation to help us loosen the self-centered stronghold of resentment.

Kongtrul Rinpoche also reminds us of the teachings of karma – that nothing happens by chance and every effect has its causes. Sometimes the connection between cause and effect is immediate and obvious, but more often karma is “too intricate and far-reaching for ordinary beings like ourselves to be able to comprehend it fully.” When we feel this tendency to want to repay an injury, get even in some way, we are laying the seeds for a mutually destructive pattern and its potential to go on and on. We put an end to this cycle by opening the heart of tsewa and forgiving. But, he cautions, this only works for those who genuinely want to get over their grudges.

In another chapter Kongtrul Rinpoche addresses the common notion that if we open our heart and become tender, we will be taken advantage of and, in essence, “turn into a doormat.” To this he replies, “A bodhisattva is not a doormat,” and “bodhisattvas have boundaries.” Even the Buddha had to say “no” at times and in doing so, caused others pain. Behaving naively with others will not help them nor advance our own spiritual progress. We do not act blindly with simplistic good intentions. He writes, “The Dharma does not defy common sense.” We need not surrender the positive aspects of our conceptual mind – our critical intelligence. As we develop wisdom and compassion, we see how our critical intelligence complements our tender heart making our actions more beneficial to others.

Relationships, Rinpoche says, can be tricky; there are many ways we can go wrong. He writes, “In some sense, it comes down to protecting our heart from our head . . . We would like somehow to mold relationships and people according to our preferences.” We need to recognize and overcome our tendency to see the other person as an extension of ourselves rather than an individual, a fellow sentient being who also wishes to be happy and free of suffering. Rinpoche also acknowledges that some relationships are not workable, at least not in this lifetime. The causes and conditions are simply not favourable and it is best to move on. Sometimes this is the most compassionate thing we can do even when it causes temporary pain.

There is so much more in this little book on tenderness. Dzigar Kongtrul elucidates these profound teachings with clarity and warmth. I conclude with his words: “There is nothing to prevent our tenderness from warming up the entire universe.”

You can purchase Training In Tenderness from Shambhala Publications here.

Christine Heming is a regular contributor to the Shambhala Times. She has been a meditation instructor and teacher of the buddhadharma for over 40 years. She was student of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and at his request moved to Nova Scotia with her family in 1982 to help establish a dharma centre in Halifax. About 25 years ago she moved from Halifax to the Annapolis Valley and founded the Annapolis Shambhala Group. She has completed a three-year retreat in the Kagyu Buddhist tradition. She loves gardening, reading, and long walks on Nova Scotia’s beaches. She lives with her husband, Gregory Heming, and their puppy, Norbu, on a farm in Port Royal, NS.

Christine Heming is a regular contributor to the Shambhala Times. She has been a meditation instructor and teacher of the buddhadharma for over 40 years. She was student of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and at his request moved to Nova Scotia with her family in 1982 to help establish a dharma centre in Halifax. About 25 years ago she moved from Halifax to the Annapolis Valley and founded the Annapolis Shambhala Group. She has completed a three-year retreat in the Kagyu Buddhist tradition. She loves gardening, reading, and long walks on Nova Scotia’s beaches. She lives with her husband, Gregory Heming, and their puppy, Norbu, on a farm in Port Royal, NS.

Apr 19, 2019

Reply

Because of this review I started reading Training in Tenderness, and it is a treasure. I had lost heart because of the revelations, and this book opened my heart to the loving kindness of the dharma again. Thank you so much Christine!

Apr 5, 2019

Reply

What a great review–and so timely! Thank you Christine!