Friday

Arts and Poetry, Featured StoriesRinpoche’s Gauntlet

By Steven Saitzyk

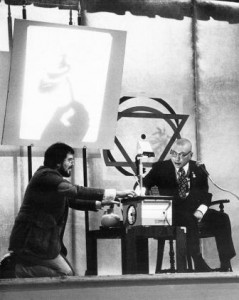

Black and white photos courtesy of Andrea Roth

In 1979, or maybe 1980, I met with a group of artists in Los Angeles about an installation. The person creating the installation was my teacher Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, though in the art world he went by Chogyam Trungpa or C.T. Mukpo. There were a few famous artists at this meeting, but the only person there with world class status was Sam Francis. His opinion was the one that mattered because all the others artists would automatically defer to him.

The real purpose of this meeting was to get a commitment from Sam that he would lend his name and support to Rinpoche’s installation. At this point we had not yet found a location, and if Sam supported it, others would freely do so and a good location would be so much easier to acquire. It would also mean that people well beyond the sangha and friends of the sangha would come to see the show. Maybe the Los Angeles Times would review it. In this city, a name like Sam’s meant the difference between getting noticed and remaining obscure.

I had a sense that Sam would offer his support, but it needed to be more than a polite, half-hearted offer. I had known Sam for a few years and he sometimes shopped at my small art materials store, which was named Ashe. I had visited his studio in Santa Monica, one of several he had around the world. Sometimes we would talk about Tibetan iconography and the Jungian principle of the collective unconscious. Sam said he knew Carl Jung. He had an ex-wife in Japan and a museum there dedicated to his artwork, so I knew he was sympathetic to someone trying to bring Eastern teachings and aesthetics to the West.

Despite our relationship, as is true for many artists, one’s reputation is like capital and lending it to someone could be a good or bad investment that reflects on one’s own career. So, his support would not be given lightly.

One of my roles in the installation project was as “go-between” — between Sam, some of the other artists, and Rinpoche. So at this meeting we were chit-chatting and sharing stories and I mentioned that I was going to Boulder to see Rinpoche and give him a report. There was a pregnant pause in the conversation, and then Sam spoke. He said he would lend his name to the installation and support it under one condition. Sam wanted me to personally tell Rinpoche this condition. Sam said, “If he f**ks up this show, I will personally see to it that he never gets another show in North America.”

I was so happy that Sam was going to support us that at first I didn’t think much about the language or the threat. It was a threat he could actually carry out. Certainly no major gallery would show Rinpoche’s work if Sam put the word out that we were a bunch of fools and ‘flakes.’ It wasn’t until the meeting broke up that it hit me — I was to carry back the good news of Sam’s support, but it was to be served up to Rinpoche as a threat with foul language.

I was so happy that Sam was going to support us that at first I didn’t think much about the language or the threat. It was a threat he could actually carry out. Certainly no major gallery would show Rinpoche’s work if Sam put the word out that we were a bunch of fools and ‘flakes.’ It wasn’t until the meeting broke up that it hit me — I was to carry back the good news of Sam’s support, but it was to be served up to Rinpoche as a threat with foul language.

I’ve often used that language myself and I had even heard Rinpoche use it several times, but never as a curse. Nevertheless, the thought of using it while conveying a threat to my guru was truly unnerving. Plus, I had f**ked up in the presence of Rinpoche once before, and I wasn’t eager to do it again. It had been such a mind-bending and painful experience.

It was 1975 when I messed up. Rinpoche had just finished giving a talk at the International Buddhist Meditation Center in Los Angeles, and I was doing the recording for it. As was usual for the time, a procession of people had formed in front of his chair to greet him at the end of the talk. There was some issue with the rooms and the recording setup and I was giving instructions to the setup crew. I was way too loud. I needed to know if Rinpoche wanted to give tomorrow’s evening talk in the same room or another room at the center. Without thinking, I butted into the front of the line to ask him what his preferences were.

He was seated in an armchair on a slightly raised platform. Because of an old spinal injury I sometimes have difficulty with balance and when I noticed the arms of the chair, I thought I’d rest my hands on them for support as I leaned in to talk to Rinpoche. As I did this, I immediately sensed that this was not a good idea. I felt like I had somehow trapped him in the space of the chair, but doing something to correct the situation was slow to arise in my mind. All the while, he and I continued to have a perfectly normal conversation about where to give the next talk and such. But there was this rapidly growing and expanding discomfort. Suddenly, in a very quick motion and without interrupting the conversation, he tapped his finger on the fleshy part of my right hand. I instantly withdrew both hands from the chair, despite some difficulty balancing. We finished the brief conversation quite normally and I returned to my equipment thinking that the evening’s events were over.

But my discomfort continued to grow. The cause of it seemed to be one small spot on my right hand where I could still feel Rinpoche’s finger pressing into my hand. There was nothing to see if I looked at it — there was only the distinct feeling of being touched. What started out as discomfort was rapidly becoming a nauseatingly bottomless pit in my stomach. I tried to rub away the feeling on my hand, to no success. I tried to reassure myself that it was all in my head and would go away once I had something to eat and drink. No such luck. A thought lit up in my mind like a flashing Las Vegas neon sign: I had f**ked up. I had really f**ked up.

I told no one. I already felt like a complete idiot, so why confirm it? As I went to sleep that night, I rationalized that I could sleep it off and his finger would be gone in the morning. It would be a new day and a fresh start.

The next morning, during that time when you are just waking and don’t even know where you are or even who you are, my first conscious experience was Rinpoche’s finger still pressing on my hand. As you might imagine, I was freaked out. I realized that trying to figure out whether it was real or imaged didn’t matter since the message was abundantly clear: I was too loud, too arrogant, aggressive, controlling, and disrespectful and I could not undo that. I had seriously f**ked up. I decided that when Rinpoche gave his next talk, I would keep a respectful distance. I would still do the recording, but would get someone else to pin on his lavaliere microphone.

The next morning, during that time when you are just waking and don’t even know where you are or even who you are, my first conscious experience was Rinpoche’s finger still pressing on my hand. As you might imagine, I was freaked out. I realized that trying to figure out whether it was real or imaged didn’t matter since the message was abundantly clear: I was too loud, too arrogant, aggressive, controlling, and disrespectful and I could not undo that. I had seriously f**ked up. I decided that when Rinpoche gave his next talk, I would keep a respectful distance. I would still do the recording, but would get someone else to pin on his lavaliere microphone.

It was evening at the center and I stuck to my plan. I hung out with the recording equipment, which was off to Rinpoche’s left and a little behind him. The talk was about to begin and his finger was still pressing. My one hope was that maybe when he left town, his finger would also leave.

Before beginning his talks, Rinpoche would clear his throat to test the sound system and to signal the start of the reel-to-reel taping. The sound person would always have their headphones on and volume turned up because sometimes his throat-clearing was very quiet. So there I was — out of view, with my headphones cranked way up — and suddenly I hear a tiny voice. It is unmistakably Rinpoche. No one else can possibly hear him. He says, “Are you all right?” and turns his head toward me, beaming a smile.

In that moment, the feeling of his finger pressing on my hand disappeared. The churning, groundless pit in my stomach vaporized. I returned the smile and nodded yes. Rinpoche turned back to the audience, cleared his throat, and I turned the switch to start recording. My mindless actions and the disrespect to my teacher was a mistake I promised myself to never make again.

But here I was, carrying a foul-mouthed, aggressive message to my teacher. My fear was that, if I delivered it incorrectly, it could send me to same hell realm as before. While there was some kind of personal irony in the message itself, I kept telling myself I should not be so focused on me. The task at hand was not about me. But it was hard not to be self-reflective because every time someone asked about the meeting and what I was going to tell Rinpoche, they would immediately respond with, “You can’t say that!” “You cannot say that to your teacher!” “It’s completely inappropriate!” People were telling me to edit the message. But, I reasoned, wouldn’t that suggest I did not trust my teacher to see the truth of the situation? My editing would certainly change the weight the message contained.

I wondered how many leaders had failed in their mission because the people they trusted were afraid to tell them the truth about reality, choosing instead to hide it from them instead. But at the same time, I worried that using such language, coupled with an aggressive threat, would show disrespect to my teacher all over again.

I arrived in Boulder and was debriefed by the Vajradhatu board member in charge of Dharma Art and his assistant. On giving my report, they responded in a way that echoed everyone else: “You can’t say that.” My goal was to serve my teacher as best I could. And I had been around long enough, even in 1980, to know that frequently what a student thinks is the best way to serve their teacher is not always the best way and sometimes the worst way.

The day came to present Sam’s message to Rinpoche. I still did not know what I was going to say. The board member, his assistant, and I entered what was called “A Suite,” where Rinpoche’s office was in the Boulder center. My heart always pounded on meeting him, but it was much worse this time — I could hear it in my ears. Rinpoche kindly offered me a seat near his desk, and the other two sat behind me. We talked about things in general and then the moment came when he asked how the installation project was going in Los Angeles.

I had to say something, but what? I turned to look back over my shoulder at the two other people in the room. I was definitely looking for something: last minute guidance, encouragement, even rescue. But as we exchanged looks, I realized I was on my own. At that moment their faces turned white, I think they knew what I was going to say before even I was conscious of it.

I had to say something, but what? I turned to look back over my shoulder at the two other people in the room. I was definitely looking for something: last minute guidance, encouragement, even rescue. But as we exchanged looks, I realized I was on my own. At that moment their faces turned white, I think they knew what I was going to say before even I was conscious of it.

I turned back to Rinpoche and said “I was asked to convey a message to you, sir. I was asked to tell you that if you f**ked up this show, they would see to it that you never get another show in North America.”

The room was silent. I was terrified — everyone should have been able to hear my heart pounding. Rinpoche slowly rose from his chair. He stood straight. He formed a fist and raised his hand high in the air. It all seemed in slow motion until he suddenly crashed it down hard on the desk and there was an enormous bang. The desk, the room, and all of us seemed to shake, and then he shouted one word: “GREAT!”

While there were many difficult challenges we had to face in order to manifest this Dharma Art installation, the way Rinpoche picked up the gauntlet Sam had thrown down without any hesitation whatsoever gave us courage to meet them. What we had all perceived as a threat was truly inspirational to him. The show took place at the Los Angeles Institute for Contemporary Art and was an enormous success. One of the top art critics of the Los Angeles Times gave it a very positive review. Over the course of the 3-day exhibit, hundreds of people were frequently lined up around the block to get in. We even had to regulate the flow so the installation would not be overwhelmed. It was the best attended installation of its kind in the history Los Angeles and was documented in the video, “Discovering Elegance.”

There were many lessons in these two experiences for me, including the way humility and courage can work together. On a deeper, more personal level, the lesson was about joining the visceral, felt sense with the thought sense of the situation, what I think I know. For me, they are not always working in concert, and when I act on only my felt sense or only my thought sense, I get into trouble. If I go with just my gut, I end up acting blindly and out of ignorance. If I use just logic, I end up with a lot of thoughts about thoughts, which are divorced from experience. But when they are in concert, informing each other, thoughts and experience seem to turn into knowledge, understanding, and skillful action. How do they come to work in concert? For me, it is a matter of repeatedly coming back to square one — to my felt sense and then listening to the first thoughts that arise from that direct experience. Because those thoughts are based on what is happening, they are often true to the moment and filled with the potential for skillful means.

Sep 8, 2012

Reply

This is a wonderful story – has so much to offer about working with others and ourselves. Thank you, Steve, today ( 2012) for being there, then and now, to live this story, to struggle with the challenges, and to receive the touch and the smile that relieved the touch. (I might say: the blessing). Thank you for taking the Time to tell the story and to pass it on. The gift is in the question – the treasure is in the story. I’ve seen “Discovering Elegance” several times over the years, (Warrior Assembly 1997, and SA Art intensives when Steve showed it) – the story Steve told here adds more discoveries to it, adds elegance, and has folks saying: “Where can we see photos and how to see video” See? More gifts and more treasure. Here’s to life, discovery and elegance.

Mar 28, 2012

Reply

Unfortunately that was the only picture I had and it was a gift from Andrea Roth. There was a great video of the entire show in Los Angeles called “Discovering Elegance.” For some reason it is no longer available. I have asked the producer to reissue it or at least post it on youtube but have never received a response. Some of us still have old VHS tapes of it. I show it whenever can at Shambhala Art programs and at my class on meditation and the creative mind at Art Center College. People find it is very inspiring.

Dec 29, 2009

Reply

Yes there are photos of the installation process.

I shot photos in black and white, mostly. Andrea Roth and I both took photos but Andrea also took more formal shots of the installation flower arranagements too, if memory serves me. We also had a joint photo exhibition of our photos set up in a long corridor during that time. They were packed up and set to Halifax where I think the photos were all attributed to Andrea.

The photos I took are with me in my personal photo library , some I sent to … well, some are out there. From the opening Lasang that began the construction that was headed by Herb Elsky to the end.

A book. What a very nice idea on this subject. …and of course many peole helped on the set up, from finding the right objects, to making tatami mats and pulling all nighters. … and lots of contact with Rimpoche.

Lots of people came from Boulder and New York to assist.

Dec 16, 2009

Reply

I would be very interested in seeing any photo documentation of this historic event, the installation at the LA Museum by Chogyam Trungpa. Please advise where i might find any info regarding this. If a book has not been made of this event, I ask, why not?

Thanks

Oct 25, 2009

Reply

It is unfortunate that the only photos you used for this story were pictures that included yourself. Are there no other pictures of the Los Angeles installation? If so, please include them. By the way, there is an interesting documentary about Sam Francis recently completed. Did Sam like the show? What did he say about it? Did Sam Francis and CTR ever meet? Did they speak? Did they ever collaborate?