Thursday

Mandala Projects, World, otherInterview with Lee Weingrad of Surmang Foundation

Surmang Monastery, in eastern Tibet, was founded 600 years ago by the first of the Trungpa lineage holders. Until 1959, Surmang was the seat of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

Today, Surmang is one of the poorest regions in the world; local people have an average annual income of $US 50. Mothers die in childbirth at one hundred times the rate of women elsewhere in China, on average. Fewer than two out of every three babies born survive infancy.

Since 1988, the Surmang Foundation, founded by Lee Weingrad who is a student of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, has been working to bring basic healthcare and now communication to the region. For more information on the work of Surmang Foundation, visit their website here.

This interview was conducted by the daughter of one of the Foundation’s advisors and former volunteers, for her high school project.

Why did you create the Surmang Foundation?

It came into existence because of a trip I took there in 1987. I don’t know exactly why I went or wanted to go, except that I think that I wore out the chapter of my life I had lived up to that point in Boulder. Oddly enough, I could see this coming three years before.

I wanted to see the place where my Buddhist teacher Chogyam Trungpa was from. I wanted to walk where he walked. I wondered what happened to those people. What do they look like? What do they do? I wanted to meet people who knew him.

What does the monastery look like?

As it was, despite my attempts to go the year before, my trip coincided with Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s recent death, and the local people there had no closure on that event, which was cataclysmic for them as it was for us. Besides my own mother and father, Trungpa Rinpoche is the most important person, the biggest influence on my whole life.

It was a very difficult trip and I remember our jeep being stuck in the freezing Mekong River for four hours. I went there with photos of Trungpa Rinpoche, hundreds of them, videos, and scriptures he translated, scriptures he wrote. Everywhere I went there were hundreds of people lined up, all alternatively crying or laughing. It was devastating for me and at the same time oddly funny, like waking up with mice running all over my body. I even wrote a poem about that, “Homage to the Lineage of the Surmang Mice.”

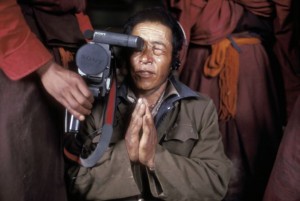

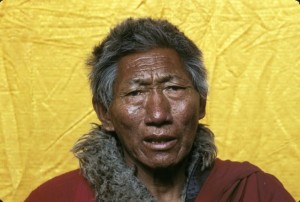

Tashi, Regent Abbot of Surmang Dutsi Til, the first person Lee met at Surmang. “He was my grandfather, my teacher, and also my vajra brother. He died in 1990.”

I had a firm conviction when I left the place after that visit that I would be back. And I did, visiting it over twenty-four times since, and moving to China to accomplish the goals of the foundation and meeting the woman who would be my wife in the process. In going there, it was like dying, my whole life flashed before me and made sense. I thought I reached my destination. Little did I know I just came to the bus depot.

Over the years I’ve seen that this place is powerful for nearly all 100 of the volunteers who’ve worked for the foundation. And it is certainly that way for me, right up to the present moment.

Why is rural health care such a concern for you?

I think that in an area like Surmang, what they call the “ultra-poor” catchment, where we are dealing with people who earn less than 14¢/day, everything is a concern: health care, education, economy, religion, politics, even art.

The question is, what is there, what’s available that you can do anything about? It was clear to me that not only was health care essential, but that the other elements of concern would not be possible if the health care issues were not addressed. How can children learn when they are constantly ill? How can there be an economy when catastrophic illness can bankrupt a family? Or can someone work or even play when intestinal parasites steal their nutrients and never allow them to feel well? With infant and maternal mortality at world-record-high levels, how can someone have the hope of attaining enlightenment when they don’t have a body? Or how can you practice meditation when you are weak or ill? How can you worship the feminine when women have such low status?

I saw the health care issue as being a kind of accident scene and in that case we needed to stanch the bleeding. As Lord Atisha said, “Work on the greatest difficulties first.”

So I saw health care as not only something essential, but it turned out something I could actually work on. We got a foundation, a warm reception from the Chinese Government, and finally funding. Our initial funding was from the Catholic Church.

What have you found to be the most effective way to reach out to the Surmang community?

Definitely by first abandoning any kind of idea of changing the culture or making them better. Being able to accept them as they are means having to investigate, even informally and personally, who they are. Not looking down on them and not putting them on a pedestal either. Loving them, their holy place, but not romanticizing it or them. Being open to them, in their glory, their everyday-ness, warts and all. This is the way Trungpa Rinpoche taught us buddhadharma, and that is the way I wanted to work.

As Kobun Chino Roshi advised me before I went, “Don’t get lost in history.”

Second, by having their own people be the providers of care. This is the road to not only sustainability, but also if you have anything worthwhile to contribute, to have it enter their society in a way they can accept. Otherwise, when it has a foreign face, it always come from on high. We did this primarily with having two local doctors, Phuntok and So Drogha, run the clinic.

Next we created a corps of Community Health Workers who could be the limbs, eyes and ears of the clinic, teaching health education particularly to the pregnant women and for new borns. Giving advice, referring people, especially the nomads, to the clinic. Being able to articulate the opinions and needs of their patients to the clinic and to the foundation.

All photos used by permission only ©2009 Lee Weingrad, all rights reserved.