Friday

Arts and PoetryLhadrima: A Painter’s Journey

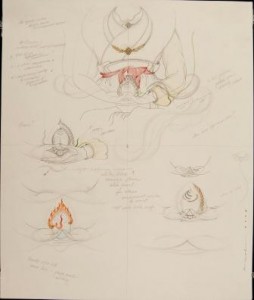

A Western Woman’s Journey as Painter of the Lha: The Noble Conquerors.

By Cynthia Moku

It was 1969 in San Francisco. I was a student taking classes at the San Francisco Art Institute on Russian Hill and the San Francisco Academy of Art on Sutter Street where, one Christmas season, some of my fashion drawings hung in the window of Macy’s department store on Union Square. Painting thangkas (scroll paintings of buddhas) was the last thing on my mind. In fact, it wasn’t even a blip on the radar screen. Yet, the mid 1960s in the San Francisco Bay Area was a time and place for groundbreaking explorations on all levels, personal, communal and cultural. Immediately following my school years within this revolution of eastern culture and philosophy landing on western shores, I would receive training as a teacher in the Iyengar method of hatha yoga. Coincidentally, I would be introduced to the shamatha and vipashyana practices of the Burmese Buddhist insight meditation tradition.

Fast forward to 1973: the great Rimé meditation master Kalu Rinpoche, holder of the Shangpa Kagyu Buddhist teachings transmitted by the two wisdom dakinis, Sukhasiddhi and Niguma, stayed at my home on his first trip to the United States. The following spring after Rinpoche’s visit, I was sitting next to Glen Eddy as he demonstrated brush line drawing, one of the techniques engaged in the process of thangka painting. Glen himself had just begun drawing and painting for Tharthang Tulku Rinpoche. In the summer he would begin doing brush-line ink drawings for Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. They would appear in the Vidyadhara’s early books, such as Cutting through Spiritual Materialism.

Over the next year-and-a-half, I practiced drawing the Buddha’s face, hand gestures, and full body, both male and female forms. I painted a small thangka of Chenrezig (Avalokiteshvara), which a Mongolian Buddhist lama purchased, to my absolute surprise. Glen had shown me the correct proportions of a Buddha figure on which all other figures are based. He had demonstrated brush line drawing and the various techniques of filling in color, shading and laying gold for the painting process. Lama Kunga Rinpoche asked me to do some drawings for his early publications, and I did small drawings for other teachers as well. A few lamas began to suggest that I teach at their centers. I thought this was a rather misguided idea. My experience was minimal, to say the least. I was also primarily focusing my attention on my new role as young mother and wife, taking care of my family.Still, I found that drawing the Buddha was what I did, when I had time. I always turned to it. My toddler children and their playmates would sometimes color copies of my drawings for fun. Despite the struggles such an exacting drawing technique brought up for me, an underlying freedom and peace arose, even amidst the restraint and compliance. The synergy of such contradiction is never logical.

When Kalu Rinpoche came again giving teachings throughout Canada, the Unites States and Europe, I mentioned to him that some of the lamas were asking me to teach thangka painting. I also explained why there was no sensible reason that this should be even a consideration. Rinpoche listened patiently as he sat cross-legged on his bed. When I was finished, he simply whispered, “It would benefit many beings.”

I distinctly remember experiencing several moments of frozen panic when I heard this reply. As a result, I did not leap at his suggestion readily. In fact, I tried valiantly to convince myself that Rinpoche’s answer to me was, “No, you should not teach.” After some time I had to admit that what he had said so simply to me could only be construed as a “yes”–and for the benefit of others no less. The cozy “benefit” of satisfying my small mind, which was happy to remain anonymously content, found no ground to stand on. I was scared.

…and this is where the real story begins…

As I tentatively accepted invitations to teach the art and techniques of thangka painting (the first occasion being through an invitation from Lama Ken McLeod, the highly regarded dharma teacher and translator at Kalu Rinpoche’s Los Angeles Dharma Center), I found that people were very curious about why I was interested in doing this type of art, seemingly so disciplined, with no room for self-expression, following strict historical canons and rife with symbolism. The meaning of thanka paintings for the most part remained unknown and without translated sources at that time–the early 1970s. Moreover, here was a young western woman being asked by Tibetan lamas to do simple works for them. This seemed so cool and unusual, but people wondered, as an “artist,” why are you doing this?I had to look into my own heart and mind, my intuition and reason, to answer this question truthfully. With support and encouragement from my husband who was also drawing and painting, I began learning about these works of art viewed through the lens of being part of a historical religious tradition. We collected museum catalogues and prints of Himalayan Buddhist art. They were very limited at that time, nothing like the wealth of material available to us now. I began to look more discerningly at thangkas and prints of thangka paintings from the past. I looked carefully at the compositions, the colors, the brushstrokes, the hand gestures and postures, especially the faces of the buddhas. It became very clear that there were true works of art in this tradition of painting, and there were many that were not.

The Karma Ghadri or eastern Tibetan painting school was the source lineage of my training received from Glen. This school is highly influenced by the atmospheric and spacious refinement of Chinese painting, and I resonated naturally with this. I saw how the Karma Ghadri paintings of the late 17th to 19th centuries were often true classic works of art, as moving as the works of Michelangelo, Rembrandt and Manet. The artists of this illustrious Kharma Ghadri period, nameless to us now, were real people breathing along with their brushstrokes like any other painter. They were clearly devoted to the dharma and its message of truth. They were capable of expressing the living qualities of these enlightened beings even within the discipline of an exceptionally stylized form of painting. They were highly skilled and also remarkably sensitive and pure in their execution of brush and choice of color and compositional elements. I had less and less interest in the majority of thangka paintings that did not hold such a caliber of excellence.

I read what I could find on the history of Himalayan Buddhist art and the artists, of which very little is recorded. I asked the rinpoches and lamas that came to our center in San Francisco questions on the subject. Through their answers, through the teachings they so generously poured on us, and through their guidance in the practice of meditation, which I tried to do regularly yet still fumbled, pieces of the puzzle began to emerge. This passionate curiosity continues to this day. The visual story, the illustrated dharma held within the symbolic language of thangka paintings, unfolds itself more with every contact both with the realized masters and with the communities of meditation practitioners in which I have been involved.

Feb 25, 2014

Reply

Cindy,

Are you artist that Jack Thopmson knew in Sausalito??

Cal