Wednesday

Dharma TeachingsA Picture of the Sky

Celebrating a collaboration between Naropa University and the University of Colorado on a Buddhist Studies Lecture Series in honor of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

…a course at the University of Colorado – Winter, 1971 (see part 1 here)

Part 2

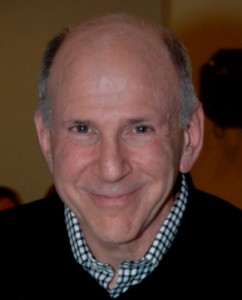

by John J. Baker

…But there is another subtler way to understand the trikaya, and it is this understanding that Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche taught to us that winter day in 1971. He did it in this way.

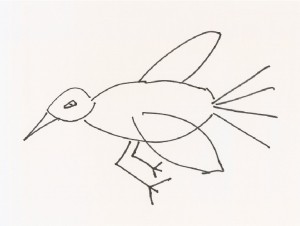

Stepping to the blackboard, he picked up a piece of chalk and drew the following figure:

Then he stepped back and asked: “What is this a picture of?”

Of course, no one wanted to say the obvious, and there was an extended silence, until finally some fellow raised his hand and said, “It’s a picture of a bird.”

Rinpoche replied, “It’s a picture of the sky,” and in those six words he taught the entire trikaya.

Rinpoche was introducing us to the most profound Buddhist description of reality, as it arises in the only place and time it ever arises: here and now. It is not a metaphysical explanation of reality; it is simply a description of what arises in the moment, now, the only time we ever have.

The past and future are mental constructs. Even the present can be conceptualized, but it can also be experienced. In fact, we choicelessly experience it all the time. It is merely a matter of whether we emerge from our dreams about the past, present, and future long enough to notice and see it clearly, truly.

And in the present the six types of phenomena – sights, sounds, smells, tastes, tactile sensations, and mental events – the six knowables – arise and pass away, a constantly appearing and disappearing display, like a movie, like images passing through a mirror. These “things” do not endure, even for an instant, in the present moment, as we turn our head, as our attention shifts, as the light changes and things move, the display is constantly in motion, changing so completely and continuously that we cannot even point to something that has changed. It is a continual “presencing” as they say in the dzogchen texts, a presencing of what we call phenomena. And this display has three aspects.

First, the dharmakaya aspect. All phenomena seem to arise from and pass back into nothing. Where did that sound go? That precise visual experience with the light and the angle of view? That thought? That odor? They arose from nowhere, appeared in the midst of a concatenation of conditions, and finally disappeared into nowhere. That fertile “nowhere” is, in this first pass at definition, a meaning of the dharmakaya, absolute reality and the “womb” from which all appearances arise and the charnel ground into which they pass away.

And yet, some thing seems to appear and pass away. This “thing” aspect is the nirmanakaya. There is a “presencing” of phenomena (the six knowables appear). That presencing is the fact of seeming appearance, the “thingness” of appearances, and it is all that confused sentient beings know, because they are not paying attention to the present moment, not noticing that nothing truly exists but is a mere “presencing.”

Confused sentient beings see the phenomenal world through the veil of static thought: one sees a chair, a person, hears a piece of music, and one is consumed with the pastness and futureness of it all, one is in relationship to it, an I/other proposition, fraught with past and future significance for “my” well being. As long as we (literally) think that other things and I exist, life must be experienced as a series of I/other problematic relationships. If the other is antipathetic to us, causes us pain and unhappiness, then we want to push it away from us: hatred. If it promises pleasure, happiness, security, etc., then we wish to pull it to us: desire. And if the other promises neither benefit nor harm, then we don’t care about it: indifference. In Buddhist doctrine, these are called “the three poisons,” and you can find them depicted at the center of the Wheel of Life, a heuristic depiction of confusion, as a snake, rooster, and pig, respectively.

But seen stripped of concept, nakedly in the present moment, in reality beyond even the present moment which can be a concept in itself, then the nirmanakaya is an aspect of the presencing, of the display, its seeming “thingness,” and it is described as the display of compassion, because it can communicate with us in the form of a teacher (an actual human being or simply life experiences which move us along our path).

And finally there is the sambhogakaya, which refers to the aspect that, as these “things” arise and pass away, they communicate to us what they are: the redness of red, the sweetness of sugar, the cold of ice, the sadness of sorrow. It is precisely because all phenomena are arising out of nowhere and passing away into it again, because they are utterly transitory, that they can and must express their qualities, so vividly and beautifully and meaningfully. This is the sambhogakaya, and it is the realm of magic: not magic in the sense of walking through walls or reading minds (although there may be that, too), but magic in the sense of the extraordinary beauty and meaningfulness and value of this world seen nakedly, stripped of the false, ego-centered and emotion-laden thoughts/dreams through which confused sentient beings see their lives. Sambhogakaya is the world of deity – sacred world. In confused world things are of greater or lesser value in terms of what they can do for or to me. In sacred world things are of value for no reason at all; this life has intrinsic worth.

And so, seen in the present moment, a bird is utterly insubstantial: a constantly changing presentation, a presencing from the ground of nothingness, coming into being and passing away so totally every instant that we cannot even find any “thing” that is coming into being or passing away. In fact, we cannot distinguish between the bird and the nothing (symbolized here by the sky), which is its womb and grave. So when Trungpa Rinpoche said that he had drawn a picture of the sky, there were two ways to take his assertion:

First pass: We are so focused on the thing that we do not pay attention to the background (temporal as well as spatial) from which it arises. Look! The bird is also a picture of the sky! Lost in concept, seeing the world through the veil of discursive thought, we have been ignoring the ground from which phenomena arise and into which they disappear. In fact, this is one meaning of the Sanskrit word avidya (usually translated as “ignorance”), the fundamental error which produces unenlightenment or confusion. Trungpa Rinpoche said that avidya means “ignoring” or not seeing (the literal meaning of a-vidya) the ground, focusing only on the figure and its significance for or against me.

Second pass: the bird and sky seem different and yet we cannot find the dividing line between them. They create each other and are each other. The bird, as it moves through the sky, is merely a recoloring of the sky in an infinite number of locations. The difference between them is merely seeming, just like an image in a mirror. In the highest tantric teachings the word “sky” is often a code word for and interchangeable with “space,” which signifies the unity of the three kayas.

In vajrayana (tantric Buddhist) practice one often recites this two-line formula, or some variation on it: “Things arise, and yet they do not exist; they do not exist, and yet they arise!” The first is what Buddhists call the “absolute truth”; the second is what Buddhists call the “relative truth.”

Finally and always, the three kayas are merely different aspects of the same thing, which is what is meant when in the texts we find the assertion that the three kayas are one. The nirmanakaya and sambhogakaya, often lumped together and called the “rupakaya” or “form body of the buddha,” are in union with the dharmakaya, the absolute body, from which – in the present moment, here and now – everything seems to arise and pass away.

Things arise from and pass back into nothingness: dharmakaya. Things arise from and pass back into nothingness: nirmanakaya. And as those things arise and pass away, they communicate their unique, brilliant, emotionally moving individuality: sambhogakaya.

To quote a line from Trungpa Rinpoche’s Sadhana of Mahamudra, “Good and bad, happy and sad, all thoughts vanish into emptiness like the imprint of a bird in the sky.”

“It’s a picture of the sky.”

~~

This history was composed to celebrate a collaboration between Naropa University and the University of Colorado on a Buddhist Studies Lecture Series in honor of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. The annual lecture brings scholars of Buddhism to Boulder to give a lecture, free and open to the public, hosted on alternating years by Naropa and CU Boulder.

This year, John Makransky of Boston College will be delivering the second annual Chogyam Trungpa Lecture in Buddhist Studies at Naropa. For more information, visit this website.

Please help endow the Chogyam Trungpa Lecture Series with a donation.

John Baker has been a student Buddhism for more than 41 years. A close disciple of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, he co-founded and taught at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, serving as its CEO for the first three years of its existence and teaching Buddhism there for five. He also co-founded and co-directed the Karma Dzong Meditation Center in Boulder for the first five years of its existence. He is the co-editor of Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism and The Myth of Freedom and author numerous articles. After 23 years in private business, he retired in 2000. During this time he continued teaching Buddhist thought and meditation practice throughout North America, delivering lectures, weekend programs, and multi-month courses. Today he is a senior teacher in the North American Buddhist community and at the New York Shambhala Center and the Westchester Buddhist Center, of which he is a founder. He has led a number of month-long meditation programs at Shambhala Mountain Center in Colorado and Karme Choling Meditation Center in Vermont and has taught at the Vajradhatu Seminary. John lives in Manhattan where he trades options and enjoys coaching part-time. His younger daughter, Olivia, lives with him half-time. His adult daughter Cara, son-in-law Vajra Rich, and granddaughter Stella, live in Boulder, Colorado.

John Baker has been a student Buddhism for more than 41 years. A close disciple of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, he co-founded and taught at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, serving as its CEO for the first three years of its existence and teaching Buddhism there for five. He also co-founded and co-directed the Karma Dzong Meditation Center in Boulder for the first five years of its existence. He is the co-editor of Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism and The Myth of Freedom and author numerous articles. After 23 years in private business, he retired in 2000. During this time he continued teaching Buddhist thought and meditation practice throughout North America, delivering lectures, weekend programs, and multi-month courses. Today he is a senior teacher in the North American Buddhist community and at the New York Shambhala Center and the Westchester Buddhist Center, of which he is a founder. He has led a number of month-long meditation programs at Shambhala Mountain Center in Colorado and Karme Choling Meditation Center in Vermont and has taught at the Vajradhatu Seminary. John lives in Manhattan where he trades options and enjoys coaching part-time. His younger daughter, Olivia, lives with him half-time. His adult daughter Cara, son-in-law Vajra Rich, and granddaughter Stella, live in Boulder, Colorado.

Copyright John J. Baker 2014

Sep 22, 2014

Reply

Thanks for sharing this teaching, John. I was in one of those CU classes taught by VCTR–the one in which he taught the 12 nidanas. Rinpoche was so playful, brilliant, and concept-blowing. Even when he was talking about the Hinayana, you’d get this bigger hit, bigger view, with his sense of humor and delight to be teaching Western students. Yet, as you indicated, he made no promises. The path was always up to us.