Sunday

Arts and PoetryWithout Beginning or End, Part 3

A multi-part series on the trans-temporal art of Yeachin Tsai

by Robert R. Shane

V. The Time of Compassion

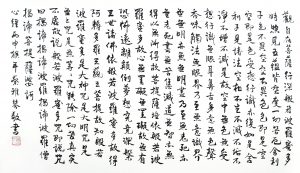

This profound interconnection of all things is expressed in the Buddhist notion of dependent origination (pratīyasamutpāda). This thesis that all things exist because of other things, or what Thich Nhat Hahn calls “interbeing,”(12) is the foundation for Buddhist compassion. These ideas are evoked in The Heart Sūtra, one of the most revered texts in the Mahayana branch of Buddhism. (In the Zen tradition, it is recited morning and evening by monks.) This sūtra is a dialogue mostly spoken by the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara who embodies perhaps the greatest compassion in all of Buddhism. Following a long tradition of Chinese calligraphy, Tsai has copied the Heart Sūtra and by doing so she placed herself in the past, re-performing the strokes of earlier calligraphers, in order to inscribe the past in the present; at the same time, she contributes to the future life of the sūtra by preserving it in a new form and awakening new audiences to it. Tsai’s act of transcribing the Heart Sūtra has the temporal structure of a ritual.

The performance of ritual situates the present-day practitioner in the past while simultaneously pulling the past into the present. This trans-temporality of ritual is made possible by its iterability: the ability to repeat the movements, strokes, and words of the ritual means that even before its first performance the ritual already contains within it the possibility of its own future. Tsai’s strokes in the Heart Sūtra bind together future, past, and present in a heterogeneous yet inseparable unity. Referring to the centuries-old traditions in Chinese painting that she still practices today, Tsai has said: “Nothing is old, nothing is totally new.”(14) Dependent origination applies not only to interconnections across space, but time as well.

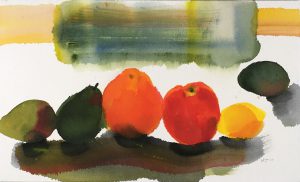

What is the relationship between the call to compassion contained in the Heart Sūtra, emptiness, and Tsai’s trans-temporal art? “Emptiness is form, form is emptiness,” is a line from the Heart Sūtra that has mystified and inspired twentieth-century artists in the United States and Europe, such as composer John Cage.(15) Emptiness in Buddhism is the realization of the interconnectedness of all things and beings. One’s self is empty of ego when one realizes she is full of the world. Tsai’s still lifes awaken the viewer to the fullness of the world inside her.

As we see the brilliant oranges, yellows, and greens and the vital forms in Tsai’s still life paintings, which are reflections of the phenomenal world, we recall philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty who wrote, “Quality, light, color, depth, which are there before us, are there only because they awaken an echo in our bodies and because the body welcomes them.”(16) In this way, the dualism between artwork and audience dissolves as Tsai’s art awakens the viewer’s own inner capacity for beauty. Shambhala founder Chögyam Trungpa described this inner capacity as a manifestation of a fundamental or “basic” goodness of being human: “When we see a bright color, we are witnessing our own inherent goodness… We can appreciate beauty…the yellowness of yellow, the redness of red, the greenness of green, the purpleness of purple.”(17) Awakening to this basic goodness in oneself and others, which Tsai facilitates through her color, was for Trungpa the first step in creating an enlightened society.

The compassion evoked in Tsai’s work, while it is not overt, it is nonetheless transformative. On the surface, compassion and ethics might seem to be the furthest ideas from Tsai’s work given her interest in modernist abstraction, the interiority of the contemplative arts, and her absence of overt political or even narrative content. But as philosopher Theodor Adorno pointed out, it is often work that is ostensibly apolitical that transforms the world politically through its sensitivity and technique which produce a radical vision.(18) Tsai describes the importance of the artist having a deep empathy with her medium. Speaking of the artist’s relation to her materials, Tsai says, “You must have a relationship with the brush as an extension of your arm and mind…a relationship with the paper as your life, knowing the paper as your friend, your stage…and you must take time to dance and meditate with your ink.”(19)

The line between artist and materials is blurred as Tsai knows them intimately; but to know them is also to understand their difference from the artist’s ego, to celebrate their own being. In this way, Tsai’s artistic practice is a model for engaging with the world and with others and moves beyond the dualism of aesthetics and ethics. This ethical-aesthetic life overcomes dualisms while embracing difference. Tsai’s beautiful and sublime forms coupled with her sensitivity to technique and materials unassumingly bring a radical change to our ways of thinking, moving us beyond the numerous dualisms and temporalities discussed here: time/timelessness, now/eternity, cosmic/microcosmic, human/inhuman, art/viewer. Tsai offers the viewer new ways of thinking by creatively confounding old ones.(20)

The shapes of the colorful fruit in Tsai’s still lifes tend to be circles, bringing us full circle back to the circles of The Contentment of Mr. Orange, the ensō, and the “Floating World” series. Abstraction and representation, calligraphy and painting—the range of Tsai’s work demonstrates not disunity, but on the contrary, a fundamental interconnectedness of visual arts practices. Tsai’s art, like the circle for Kandinsky, is “the synthesis of the greatest oppositions.” She explores the unity and heterogeneity of past-present-future and of human-inhuman providing a vital model for engaging ethically with ourselves and others. She awakens us to the beauty in the phenomenal world and within us. She teaches us how to see visually, kinesthetically, and compassionately.

Robert R. Shane received his Ph.D. in Art History and Criticism from Stony Brook University where he studied with distinguished scholars in the fields of art history and philosophy, including Dr. Donald Kuspit and Dr. Jacques Derrida. Dr. Shane is currently Associate Professor of Art History at the College of Saint Rose in Albany, New York. His doctoral dissertation was an investigation of the work of video and performance artist Paul McCarthy; his current book project is an interdisciplinary study of contemporary art, dance, and philosophy of time. Dr. Shane has completed several of the Shambhala Levels, and among his scholarly interests is the relationship between of art and Buddhism.

Robert R. Shane received his Ph.D. in Art History and Criticism from Stony Brook University where he studied with distinguished scholars in the fields of art history and philosophy, including Dr. Donald Kuspit and Dr. Jacques Derrida. Dr. Shane is currently Associate Professor of Art History at the College of Saint Rose in Albany, New York. His doctoral dissertation was an investigation of the work of video and performance artist Paul McCarthy; his current book project is an interdisciplinary study of contemporary art, dance, and philosophy of time. Dr. Shane has completed several of the Shambhala Levels, and among his scholarly interests is the relationship between of art and Buddhism.

Original works by Yeachin Tsai, all rights reserved; explicit permission of artist required for any use beyond this article.