Tuesday

Arts and Poetry, Northeastern States, Scene and HeardThe Third Mind Exhibition

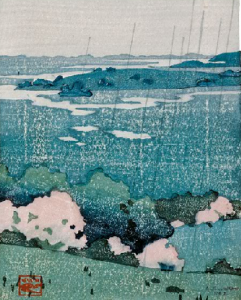

New River – watercolor series 1981- by John Cage

Ellen Pearlman, New York -based writer and editor of the Brooklyn Rail who lives part time in China, writes about The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860–1989 at the Guggenheim Museum in New York responding to the influence of eastern thought on western art. The exhibition is an ambitious academic effort to document the global narrative unfolding in a contemporary context.

From January 30 to April 19, 2009, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City presented The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860–1989, an exhibition on the dynamic and complex impact of Asian art, literature, music, and philosophical concepts on American art. It features 250 works by 100 artists in painting, sculpture, video art, installations, works on paper, film, live performance, and literary works, and draws from over 100 major museum and private collections in North America, Europe, and Japan.

The Third Mind proposes a new art-historical construct––one that challenges the widely accepted view that American modern art developed simply as a dialogue with Europe––by focusing on the myriad ways in which vanguard American artists’ engagement with Asian art, literature, music, and philosophical concepts inspired them to forge an independent artistic identity that would define the modern age and mind.

Editor’s Note: We are currently on hiatus from publishing new articles; in the meantime, please enjoy this classic item reprinted from our back issues.

These artists developed a new understanding of existence, nature, and consciousness through their prolonged engagement with Eastern religions (Hinduism, Tantric and Chan/Zen Buddhism, Taoism), classical Asian art forms, and living performance traditions. Japanese art and Zen Buddhism dominated in part because America’s political and economic ties with Japan were historically stronger than those with China or India, the other nations examined in this exhibition.

To truly understand China’s role requires a separate show focusing on the origins of Chinese influence in Japanese art and tracing it all the way to up through modern times. For most Western artists the initial pre-modern exposure they had to Chinese art was through reproductions or museum exhibitions which in North America meant visiting the first collection of Asian art assembled by the great curator Ernst Fellonosa, housed at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Beginning with the late nineteenth-century Aesthetic movement and the ideas promulgated in transcendentalist circles, The Third Mind looks at the Asian influences shaping abstract art, Conceptual art, Minimalism, and the neo-avant-garde as they unfolded in New York and on the West Coast. It also presents select developments in modern poetry, music, and dance-theater.

The title of the exhibition refers to Untitled (“Rub Out the Word”) from The Third Mind (ca. 1965), a “cut-ups” work by Beat writers William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin, which combines and rearranges unrelated texts to create a new narrative.

The exhibition is organized chronologically and thematically into seven sections:

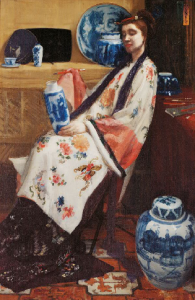

Aestheticism and Japan: The Cult of the Orient

American artists’ fascination with the East began in the late 1850s and developed from intellectual circles radiating from Boston, especially the interlocking communities of Harvard University, the Unitarians, and the transcendentalists. In the wake of Commodore Matthew Perry’s opening of Japan in 1853–54, philosophies and artistic practices of “the Orient” and especially Japan as an alternative to European sources of cultural identity came into focus. This section shows works by John La Farge, James McNeill Whistler, Mary Cassatt, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Abbott Handerson Thayer, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

Landscapes of the Mind: New Conceptions of Nature

Artists of the early to mid-twentieth century championed modern and abstract art in America while invoking Asian aesthetics and philosophies that conceived of nature as a unity of matter and spirit, transcendentalism and Theosophy. There is the work of Arthur Wesley Dow, Georgia O’Keeffe, Alvin Langdon Coburn, and Arthur Dove; the Photo-Secessionists Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz; and the painters Marsden Hartley and Stanton Macdonald-Wright. It culminates with the Northwest school of painters that coalesced in the 1930s with Mark Tobey, Kenneth Callahan, Paul Horiuchi, and Morris Graves.

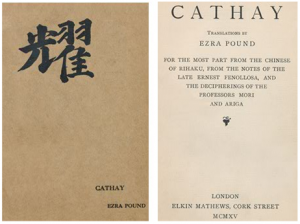

Ezra Pound, Modern Poetry and Dance Theater

Ezra Pound rewrote American translations of Japanese No plays and classical Chinese poetry, including poems by Tang poet Li Bai (701-762), a project that provided life-long inspiration for the appropriation of Asian literature as the basis for his creative method and style. Cathay (1915) established Pound as the chief innovator of Chinese poetry in English. This section also includes works by influential writers Lafcadio Hearn and T. S. Eliot , as well as highlights the history of the Japanese dancer Itō Michio who performed William Butler Yeats’s No-inspired play, At The Hawks Well (ca. 1916), which later influenced the aesthetics of choreographer Martha Graham and sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

Abstract Art, Calligraphy, and Metaphysics

By 1955, the calligraphic brushstroke, was a fundamental approach to Abstract Expressionist painting that on the pure and spontaneous gesture of the artist’s hand. The rhetoric of Zen Buddhism, which promoted direct action, allowed artists to aspire to directly record their inner visions. Artists Franz Kline, Sam Francis, Philip Guston,, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and David Smith, are included as are Natvar Bhavsar, Georgia O’Keeffe, Okada Kenzō, Gordon Onslow-Ford, Lee Mullican and Brice Marden.

Buddhism and the Neo-Avant-Garde

Zen and other forms of Mahayana Buddhism were philosophical influences in the American postwar neo-avant-garde. They include the activities of neo-Dada, Fluxus, and Happenings through the music of John Cage; the spontaneous writings of Jack Kerouac, and Allen Ginsberg.. There is a live projection of Nam June Paik’s Zen for Film (1964); work by Yoko Ono, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns. Also featured are important publications by the Beat writers Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Michael McClure, a film by Harry Smith and work by Arakawa and Madeline Gins, William Anastasi, Toni Marioni and Paul Kos’s sculpture Sound of Ice Melting (1970).

Art of Perceptual Experience: Pure Abstraction and Ecstatic Minimalism

The American art of the 1960s included contemplation and perceptual experience aimed at the transformation of consciousness. It includes work by Ad Reinhardt, Agnes Martin, Anne Truitt, Dan Flavin, Robert Irwin, the experimental cinema of Jordan Belson, and Dream House by La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela who present North Indian classical raga.

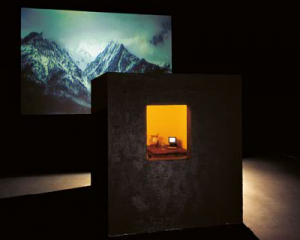

The final section presents video, installation, and live performance art of the 1970s through 1989 and reflects the growing popularity of Asian wisdom traditions in American culture. Work is shown by James Lee Byars, Linda Montano, Adrian Piper, Bill Viola, and Kim Jones. Performances are given by Gary Snyder, Alison Knowles, Meredith Monk, Laurie Anderson, Ann Hamilton and Robert Wilson.

(All images appear courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum, New York)

Oct 19, 2018

Reply

Slight correction (years later as it turns out!) A reference early on in Ms. Perlman’s review to a great curator who established an Asian component for the Boston Museum. This should read “Ernest Fenollosa,” not “Fellenosa,” a misspelling. Fenollosa and his wife had spent years in Japan where he taught at Imperial University, Tokyo. This was at a critical time. The Emperor (and government) were striving to Westernize that country. Traditional Japanese aesthetics therefore were being denigrated as second-rate, primitive, and a cultural embarrassment. Due to Fenollosa’s social contacts and his own enthusiastic collecting, he modeled an alternative view: that Japanese cultural heritage had intrinsic worth and should be preserved by all means. Strange how it took a late 19th-Century Victorian American, to stem the tide of destruction and encourage Japan’s appreciation of its own brilliant cultural forms and unique artifacts.

May 2, 2009

Reply

Regretably this article only gives the barest announcement type information about the exhibit with nothing as personal experience. It is as if the author did not actually visit the exhibit but read the public relations flyer. It was an exciting exhibition though somewhat conceptual in nature. The title itself gave no real indication of the direction of the show as The Third Mind was not at all about east meets west. The Burroughs/Gysin cutup collaboration was was indeed about creating something spontaneous and unexpected but that was not the theme of the show as it turned out. Being kind, we allow the curators the benefit of the doubt. The third thing, as in never less than two, might have been more fitting as a quote from Eliot as ‘who is it that walks beside you.’ Nevertheless it was a fine exhibition that I wish I could have spent more time viewing and returning to see. Personally, it was a group of artists who came from what I feel was from ‘my time’ and often with a similar artistic view. Even the rotunda format worked well for this, except that the elevator was out of order; at the Guggenheim one really wants to start at the top. Most of us would love to end up there as well.