Thursday

Community ArticlesBaldwin and Buddhism: Death Denial, White Supremacy, and the Promise of Racial Justice

written by James K. Rowe

This is an excerpt of an essay originally published on December 16, 2020 in The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture & Politics. The full essay is linked below.

“Terror cannot be remembered… Yet, what the memory repudiates controls the human being. What one does not remember dictates who one loves or fails to love.”

-James Baldwin

More attention should be paid to why white people remain so attached to narratives of racial supremacy. This was a sentiment shared by authors Rev. angel Kyodo williams and Resmaa Menakem in an online fireside chat held in the wake of Jacob Blake’s shooting in Kenosha, Wisconsin.1 If the purpose of radical analysis is to grasp injustices at their roots, then what might lie at the aching roots of white supremacy?

Menakem’s provocative answer, in his excellent book My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies, is that white supremacy is conditioned by generations of unprocessed trauma: “White bodies traumatized each other in Europe for centuries before they encountered Black and red bodies.”2 Left unprocessed, that trauma has helped fuel a will to racial supremacy that works emotionally to soothe people whose violent histories made them feel less-than.

A question that follows from Menakem’s powerful analysis is this: Why were Europeans dominating and traumatizing one another before their violence was directed towards Black and red bodies? In other words, is there an even deeper trauma that continues to condition a will to supremacy for white-bodied people?

James Baldwin thought so. In his powerful writings on whiteness, Baldwin argues that white supremacy is rooted in abiding terror.3 But what are white people terrified of? For Baldwin, white Euro-Americans lack the cultural resources for facing the existential reality of finitude, of death. In a powerful passage from The Fire Next Time, Baldwin observes that

“Americans cannot face reality, the fact that life is tragic. Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.”4

Although Baldwin uses collective pronouns in this passage, he concludes by specifying that “white Americans do not believe in death.” Likewise, in The Evidence of Things Not Seen, Baldwin observes that “whoever fears to die also imagines—must imagine—that another can die in his place.”5 For Baldwin, social constructions such as race and racism are mobilized as psychic buffers that help white people cope with their existential fears, albeit in infantile and destructive ways. More specifically, the fantasy of white racial superiority operates to soothe the primary vulnerability that white North Americans feel in the face of mortality. Unbearable feelings of being less-than in the face of finitude are softened with attractive illusions of being more-than vis-à-vis racialized people.

Baldwin is attuned to how race has historically been used strategically by American elites to divide the multiracial working class and to maintain class power.6 His existential analysis of whiteness, however, helps to explain why working-class whites have been so willing to choose racial over class solidarity. Gaining entrée into whiteness is a way of coping with historical trauma, as Menakem argues, but it is also a way to bear unprocessed existential trauma, particularly belittlement in the face of mortality, what the philosopher Hegel called “the absolute master.”7

For Baldwin, the ultimate hatred that white people need to overcome is the hatred they feel for themselves as mortal and vulnerable beings. If white North Americans could overcome this self-hatred by genuinely affirming human finitude, then they would be much less likely to conjure fantasies of compensatory supremacy. “White people in this country will have quite enough to do in learning how to accept and love themselves and each other,” writes Baldwin, “and when they have achieved this—which will not be tomorrow and may very well be never—the negro problem will no longer exist, for it will no longer be needed.”8

Learning from the Blues

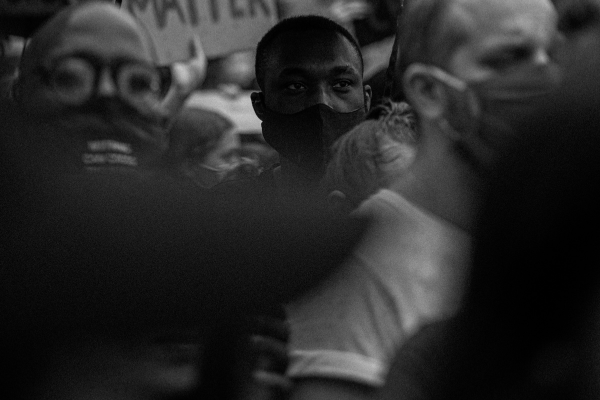

While Baldwin gestures towards the universal force of existential fear, he is sensitive to different experiences and orientations toward mortality among white and Black cultures in North America. The historical legacies of slavery and white supremacy have made premature death all too present for Black people. In an essay on blues music, Baldwin describes the realities that the blues draw from: “work, love, death, floods, lynchings; in fact a series of disasters which can be summed up under the arbitrary heading ‘Facts of Life.’”9 It is telling that the political terror of lynching is shared in the same breath as primarily existential or “natural” concerns: death, floods, meeting subsistence needs. White supremacy has overexposed Black people to the reality of finitude to the point where political violence is now part of the expected human terrain. But taking a dialectical outlook, Baldwin argues that elements of North American Black culture have managed to successfully transmute an overexposure to mortality into an honest reckoning with the existential reality of finitude, a reckoning that whites have mostly avoided.

To continue reading this article please head over to The Arrow by clicking here.