Tuesday

Community Articles, Featured StoriesHealing in the Space Between Languages and Sanghas

A personal account of Jigme Rinpoche’s Medicine Buddha Retreat at Dechen Choling

Some time in the middle of our Haligonian Winter, I received an email sent to all international desung reporting that Gyetrul Jigme Rinpoche – our Sakyong Wangmo’s brother — would be teaching the Medicine Buddha Sadhana and giving an abhisheka for the practice at Dechen Choling in the latter part of May. As soon as I saw the email, I was inspired and made up my mind to go. I had become interested in Medicine Buddha back in 2002 and had studied the teachings by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche that were available on the Internet and later became the book Medicine Buddha Teachings (Snow Lion, 2004). For many years I did the Medicine Guru practice given to our sangha by HH Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. But I also felt drawn to learning more about Medicine Buddha because of my work with intangible aspects of disease — especially cancer — through leading retreats. I booked the flight and on May 19 found myself going to Europe for the first time in 30 years. I had last been in France when I was 23, which was just before I went to Naropa University and first connected with Trungpa Rinpoche and the Shambhala Dharma.

Arriving at Dechen Choling, a bit in a daze from jetlag and a train ride to Limoge, I felt more open than usual to its extraordinarily gentle, healing energy. Green fields roll across the countryside, bordered by forests of trees that shade steeply sloping valleys which contain lovely streams. No wonder the Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche named this practice centre Dharma Place of Great Bliss, and I thought to myself, “What a perfect place to practice Sangye Menla, Medicine Buddha.”Gyetrul Jigme Rinpoche, the Sakyong Wangmo’s brother and heir to the Ripa Lineage of his father, His Eminence Namkha Drimed Rinpoche, was already in residence there and I heard that by order of the Sakyong he was to be hosted with the same respect, service and decorum of Kalapa that is normally reserved for the Sakyong himself. Acharya Mathias Pongracz served as a Shambhala ambassador, liaison to Jigme Rinpoche, meditation leader, and teacher when he was available to practice with us.

I had heard Jigme Rinpoche teach formally only once at a short evening talk he gave at our Shambhala Centre just after the royal wedding in Halifax. His talk echoed within me long afterwards, and in the following months I mentioned it in several open house talks I gave. The gist of the talk was that the Gesar lineage of the Ripa Family and the Shambhala lineage of the Sakyongs are aligned in a particular way, and he contrasted this with a conventional Buddhist approach. He said, though of course, they are not fundamentally different, the emphasis in Buddhism begins with suffering, then delineates a path that works toward the realization of suffering as inseparable from the cessation of suffering, while in the Shambhala teachings the emphasis is on Basic Goodness from the start and in the Gesar Lineage of the Ripa family the emphasis is on Celebration. Those of us who have had the pleasure to share feasts with the Sakyong Wangmo or have watched her on the dance floor know how very well she propagates the view, practice, and action of this celebration lineage with royal elegance and a creative flourish.

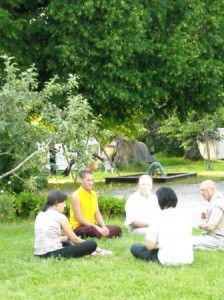

The sangha that gathered for this retreat was a wonderfully diverse mix that naturally contributed to an atmosphere of celebration. We came together through single-minded discipline and devotion. A little more than half were members of the Padma Ling sangha, Jigme Rinpoche’s students from many parts of Europe. There were also a good number of brand new students and a smattering of Shambhala sangha members of various generations and levels of practice. There was a feast of languages including Tibetan, English, French, Spanish, German, Dutch, Hungarian, Russian and probably a few more I failed to note. Though we frequently observed silence, whenever it was lifted, there were a lot of tongues shaping the airwaves in a various delightful manners.The Padma Ling sangha have always practiced in Tibetan and find that to be a true path into the practice. They regard the language, as well as the sound and experience of chanting it, to be unique and special — evoking an atmosphere of sacred space. For me, it was especially interesting to chant in Tibetan and recite the visualization section in French or English. I experienced a delightful sense of losing my language reference points. This experience led me to muse about form and emptiness in the context of dharma practice.

When Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche first brought Tibetan vajrayana dharma to the west in the early seventies, he took an outrageous and courageous leap. Part of that was trusting whole-heartedly in our Basic Goodness as students and fledgling practitioners. But he also had unshakable confidence in the Basic Goodness of the English language as a medium for true dharma. I believe that all Tibetan translations since then have been influenced, in one way or another, by his tireless and brilliant work with the translators. He really set the gold standard and because of this legacy, we practice in English with complete confidence.

I had dabbled in Tibetan a little bit back in the early eighties and have often practiced with other sanghas who use these Tibetan-shaped books with one line of text in Tibetan, a second in a phonetic transliteration, and a third in the English translation. On the one hand, I enjoy the challenge of chanting in Tibetan from the transliteration while gradually venturing to look up to see if I can follow along in the Tibetan script. Practicing this way seems to me a fairly efficient way of assimilating some Tibetan once you know the alphabet. On the other hand, however, while practicing in this way, the meaning goes out the window for anyone who is not more highly trained in Tibetan. Literal, subtle, and profound — the meaning at one layer or another is what the words are there to convey. When you have limited time for practice it seems the meaning is a priority that one is not willing to sacrifice. For this reason I have often become impatient with these types of texts for sadhana practice. Many times, I have given up on them and come back home to our good old Shambhala tradition of square books elegantly and spaciously designed with intriguing English verse and trustworthy Sanskrit mantras.

For this Medicine Buddha practice, I enjoyed the melody, rhythm, and feel of Tibetan in my ears, mouth and body as we chanted and then, as Acharya Pongracz had insisted, we read through the whole text again in English. Maybe it was just my subconscious gossip distracting me from practice, but I noted several things in this playful alternation. One was how awkward and cumbersome our chanting in English sounded when compared to the sonorous tunes of the monosyllabic Tibetan. And while chanting in Tibetan a little voice in my ear — which I of course imagined to be Trungpa Rinpoche himself but very well could have been any number of my esteemed friends and senior practitioners back in Halifax — would say: “isn’t all of this a bit unnecessary, for heaven’s sakes, we are not practicing to become Tibetologists.” And so it went, in alternation. I also noted what I thought to be the impatience of some of the other Shambhalians with the Tibetan chanting, (perhaps they had the same little voice in their ears) and a subsequent impatience (or so I perceived) coming from the Padma Ling sangha when we had to chant in the requisite Shambhala language, a bumpy cacophony of broken and desynchronized English.To continue reading, click here for Part 2.