Sunday

Featured StoriesGiving the Ghost a Voice, Part III

Coming to terms with personal identity through the spiritual practice of Buddhism

by Bryan Mendiola

Though I was not fully aware of it at the time, it was all this hatred that led me to psychology as my profession and to Buddhism as my spiritual practice. In both, there was a discipline and a path to realize my own mind and heart, to learn how to create a space in my life where I could come to terms with who I was and how I felt. Buddhism in particular provided me with a view of life that simply made sense and validated my experience of confusion, suffering, and emptiness. It allowed me also to find refuge in a life of quiet reflection and stillness that felt so natural to who I was, yet which, for so long, I had judged as deficient or unworthy. It even gave me something to be proud of in my Asian identity, as I could look upon images of a calm, wise, and beautiful Asian man who could live simply, think radically, and affect countless people. I, too, could be Buddha. Perhaps in my more naïve moments, I thought to myself that I, too, could shave my head, smile nicely, sit still, and feel worthy. As misguided as that might have been, it meant something important to me, something I had been missing for much of my life. I was learning that I could actually make a home with myself.

Moreover, Buddhism by its nondualistic, dialectical nature, gave me permission to honor all my contradictory feelings about race—both hating myself and loving myself; both identifying with race and deconstructing race; both grounding and empowering myself in identity and continually questioning it and allowing it to fall apart. Still, as I began to expand my spiritual path and embrace community, I would spend years exploring different sanghas and battling old demons of feeling different, out of place, and not understood. Time and again, I would find myself in predominantly white sanghas with predominantly white teachers, often the only person of color at a gathering or a retreat. I was very much accustomed to assimilating to white culture and acting my typical quiet, accommodating, and polite self. But with each passing year I had a longing for things to be different. At the time, I had yet to hear a teacher’s voice that resonated with my own heart, particularly when it came to issues of culture and identity.

Moreover, Buddhism by its nondualistic, dialectical nature, gave me permission to honor all my contradictory feelings about race—both hating myself and loving myself; both identifying with race and deconstructing race; both grounding and empowering myself in identity and continually questioning it and allowing it to fall apart. Still, as I began to expand my spiritual path and embrace community, I would spend years exploring different sanghas and battling old demons of feeling different, out of place, and not understood. Time and again, I would find myself in predominantly white sanghas with predominantly white teachers, often the only person of color at a gathering or a retreat. I was very much accustomed to assimilating to white culture and acting my typical quiet, accommodating, and polite self. But with each passing year I had a longing for things to be different. At the time, I had yet to hear a teacher’s voice that resonated with my own heart, particularly when it came to issues of culture and identity.

I did not have to become another silent, faceless, uniform addition to a Buddhist community. I could be myself.

What I found in the Shambhala Buddhist community was not altogether different—but it was different enough. In the local community of Boston, where I was living at the time, many other young people filled the meditation hall each week, people of various colors, genders, sexual orientations, and economic backgrounds. Gatherings were rooted in the practice of being authentic, genuine, and openhearted. While the community at large was still predominantly homogenous and white, there was a felt sense of open-mindedness and curiosity toward exploring difficult, messy topics. I was immediately drawn to Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche for his unconventional style and his openness about deeply emotional experiences of loneliness, anger, and sadness, and how transformative they can be. Here was a teacher who I felt was speaking directly to my experience as a human being, at a raw and heartfelt level. His teachings, and the teachings of his son, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, challenged me to be fully myself by not rejecting any aspect of myself. I did not have to become another silent, faceless, uniform addition to a Buddhist community. I could be myself, find my own voice, and share my own truth, with all the messiness that comes with that.

My first several years as a vipassana and Zen practitioner provided the early stability of sitting practice and the foundational teachings of Buddhadharma. I gradually learned what it meant to be with myself and my emotional life more directly. But what I also gained through my study and practice in Shambhala was how to work with my view of myself on a practical and basic level. At the core of Shambhala teachings is what is called basic goodness, a term coined by Trungpa Rinpoche. My understanding is that it points to an innate and fundamental sense of openness, purity, wholeness, and workability underlying ourselves and all of existence—what can also be thought of as Buddha-nature, egolessness, absolute bodhicitta (awakening mind), tathātā (“thusness,” or things as they actually are), and jñāna (knowledge, as in the Greek gnosis). Every teaching and practice is meant to promote awareness and trust in this primordial nature, and by doing so, we learn to not be afraid of ourselves, our experience, or the suffering of the world.

My first several years as a vipassana and Zen practitioner provided the early stability of sitting practice and the foundational teachings of Buddhadharma. I gradually learned what it meant to be with myself and my emotional life more directly. But what I also gained through my study and practice in Shambhala was how to work with my view of myself on a practical and basic level. At the core of Shambhala teachings is what is called basic goodness, a term coined by Trungpa Rinpoche. My understanding is that it points to an innate and fundamental sense of openness, purity, wholeness, and workability underlying ourselves and all of existence—what can also be thought of as Buddha-nature, egolessness, absolute bodhicitta (awakening mind), tathātā (“thusness,” or things as they actually are), and jñāna (knowledge, as in the Greek gnosis). Every teaching and practice is meant to promote awareness and trust in this primordial nature, and by doing so, we learn to not be afraid of ourselves, our experience, or the suffering of the world.

The times that I have realized glimpses of my own innate goodness have been deeply emotional and healing experiences. I’ve seen the myriad of ways that I hide from myself and from others, out of fear, embarrassment, and shame. And I’ve learned that confidently proclaiming who we are, in our full humanity, is truly an act of spiritual warriorship. At its basis, our experience is dignified, worthy, and workable. What this has meant for me is that not only are the realities of race fundamentally workable, but also that seeing and moving beyond my racialized existence is fundamentally workable. I’ve learned that the spiritual path is all-inclusive—and that I already have everything I need to continue moving forward.

As I continue to engage in dialogues in my professional, community, and home life about issues of race, culture, and identity, I see how some of my life’s deepest meaning is found in working with that which has been the source of some of my deepest pain; in ultimately facing the question in my own life of what it means to actually be seen and heard. Who am I if I am no longer invisible and silent? What story will I share of myself? What will people see and hear in it? I’ve learned that no matter what our particular cultures and identities may be, they can be both a source of power and privilege and a source of suffering and stuckness. They can keep us small and silent, and they can wake us up and empower us like nothing else, if we allow them. I believe the stories we tell of our cultures and identities, whatever they may be, can help ourselves and others to have a grasp and appreciation for the greater truth of reality. Perhaps it is the therapist in me—or maybe the Asian American Buddhist in me—but in my experience, this is how social change comes about: by unearthing and awakening that which has remained hidden within us and among us, and mourning, healing, and growing together. It is a process of embracing ourselves by giving voice to our stories—and having that voice heard and honored.

As I continue to engage in dialogues in my professional, community, and home life about issues of race, culture, and identity, I see how some of my life’s deepest meaning is found in working with that which has been the source of some of my deepest pain; in ultimately facing the question in my own life of what it means to actually be seen and heard. Who am I if I am no longer invisible and silent? What story will I share of myself? What will people see and hear in it? I’ve learned that no matter what our particular cultures and identities may be, they can be both a source of power and privilege and a source of suffering and stuckness. They can keep us small and silent, and they can wake us up and empower us like nothing else, if we allow them. I believe the stories we tell of our cultures and identities, whatever they may be, can help ourselves and others to have a grasp and appreciation for the greater truth of reality. Perhaps it is the therapist in me—or maybe the Asian American Buddhist in me—but in my experience, this is how social change comes about: by unearthing and awakening that which has remained hidden within us and among us, and mourning, healing, and growing together. It is a process of embracing ourselves by giving voice to our stories—and having that voice heard and honored.

Bryan Mendiola is a Filipino/Asian American psychologist and a student of Shambhala Buddhism. He lives with his wife and son in Western Massachusetts.

Bryan Mendiola is a Filipino/Asian American psychologist and a student of Shambhala Buddhism. He lives with his wife and son in Western Massachusetts.

Editor’s note: this story was previously published in the Harvard Divinity Bulletin, and is reprinted here by permission of the author. It was part of a segment on engaged Buddhism as a follow-up to the Buddhism and Race Conference at Harvard Divinity School in March of 2015. Videos are available online from the March 2015 conference (http://hds.harvard.edu/news/2015/03/06/video-buddhism-and-race-america-intra-sangha-racial-dynamics) as well as the April 2016 conference (http://hds.harvard.edu/news/2016/04/23/video-challenges-being-poc-largely-white-sanghas).

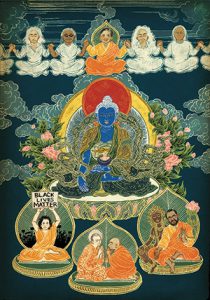

Lead illustration by Yuko Shimizu: http://yukoart.com/

May 27, 2016

Reply

Bryan what a moving post. I love your level of honesty, and relate to some of what you describe as a person who entered the mental health arena with mixed motives but delights in the complexity and challenge of self-acceptance. I also appreciate that you speak only about the mixed blessings of your experience around race without sugar-coating. I am happy that you have found a place in the imperfect family of Shamhbala.