Tuesday

Community Articles, Featured StoriesMin Thu Nya – For those who have bad character.

Mae Sot, Thailand, a border city with Myanmar.

By Larry Steele

စစ်အာဏာရှင်အောက် အမှောင်ကျခြင်း၏

ဆိုးကျိုးများ မဘသ များသိနိုင်ကြပါစေ

Of darkness under military dictatorship

May you all know the bad effects.

–Min Thu Nya, February 2025

People living under Myanmar’s military regime have three choices, according to the revolutionary Buddhist monk Min Thu Nya.

The first choice is to remain silent. This is difficult while Myanmar’s army fights a brutal civil war against ethnic and pro-democracy villages.

The second choice is to speak up in protest. The regime has arrested and imprisoned thousands, especially journalists, who make this choice.

The monastic Sangha is politically influential in Burmese culture, and the hierarchical monks are far from monolithic. Today, factions of nationalist monks support the military junta.

Min Thu Nya is not one of them. During Myanmar’s 2014 Saffron Revolution, he helped lead thousands of robed monks in pro-democracy street protests. Min Thu Nya also organized secret “Best Friend” libraries filled with novels, technical books, and encyclopedias – all later banned by the military regime. His friends started calling him “King Zero” a name that evokes emptiness and also calls for no kings…or no dictators.

“I think a lot about zero,” he says. “Is zero useless, like nothing? Some bully might say ‘You are a useless zero.’ But zero is not useless. I am a zero. We need to be empty before we can add anything.”

In February, 2021, several thousand Best Friend library books were at Wimoteti Thuka, Min Thu Nya’s monastery in Karen State. That day Myanmar’s army, the Tatmadaw, arrested Aung San Suu Kyi and overthrew her government. It didn’t take long before pro-military monks showed up at Wimoteti Thuka looking for King Zero.

Min Thu Nya and five other monks fled across the border into exile in the district around Mae Sot, Thailand.

“The final choice for people living under a dictatorship is flight into exile,” he says.

***

Min Thu Nya chose Option 3 as have more than three million Myanmar people, including the Rohingya in Bangladesh. More than 100 thousand refugees are in Thailand, in nine refugee camps heavily reliant on international aid, and confined under virtual house arrest.

Human Rights Myanmar reports that recent suspension of U.S. foreign aid has interrupted $259 million in U.S. foreign aid to Myanmar, including $45 million to support democracy, human rights, and independent media. The International Rescue Committee, a non-governmental organization, has been delivering medical services in the Thailand refugee camps, funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Those funds have dried up.

New Life, Same Teaching

Min Thu Nya is now the abbot of a very small, very humble, rural monastery outside Mae Sot. As is the practice in Buddhist communities, the nearby village provides food for the monks by way of daily alms. He has dropped his nom du guerre and identifies himself on Facebook as a “digital creator” with 90 thousand friends.

The monk has not stopped speaking. He and his friends have become content creators on Facebook, where many Myanmar people get their news. They reach a global audience by networking with groups like Save Myanmar in the U.S., the International Network for the Myanmar Spring Revolution, the Democratic Voice of Burma, Voice of Spring, and Kit Thit Media.

Min Thu Nya spends much of his time preaching to the sangha of migrant families. Many live scattered in small villages, doing informal work for subsistence wages, without official recognition by Thailand.

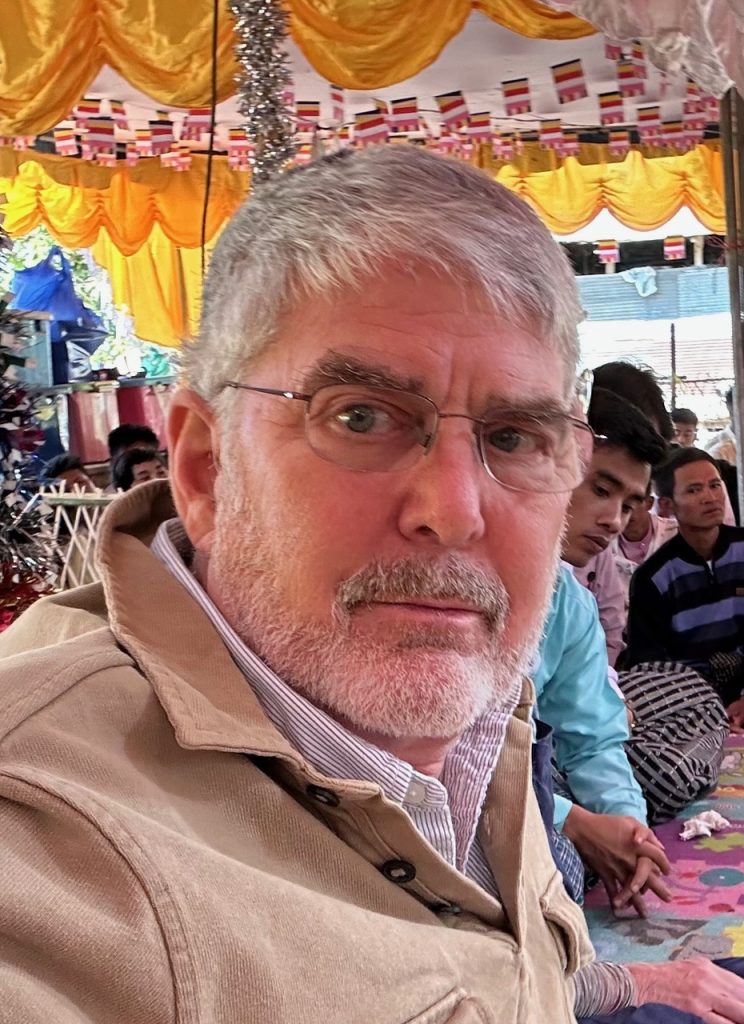

One morning the monk arrives at an elaborate red and gold gateway, the home of a traditional healer. Bikes, motorbikes and cars line the drive. A very large tent is trimmed with yellow and purple fabric that rustles in the breeze. There is a raised dais, an excellent sound system and a team of videographers. Min Thu Nya offers a dharma talk to 60 straight-backed, very present, men and women.

He chants the Metta Sutta. He tells stories from Pali scripture, from revolution, and from everyday life. He asks questions in call-and-response style, often challenging the cadre of pro-military Buddhist monks, the Ma Ba Tha, who preach in support of the military regime in exchange for gifts, money, and prestige.

“The monks who pray for the War Monsters are not teaching the Dharma,” he says. “They are people of bad character.” He asks his students, “Do you want to associate with people of bad character or people of good character?”

***

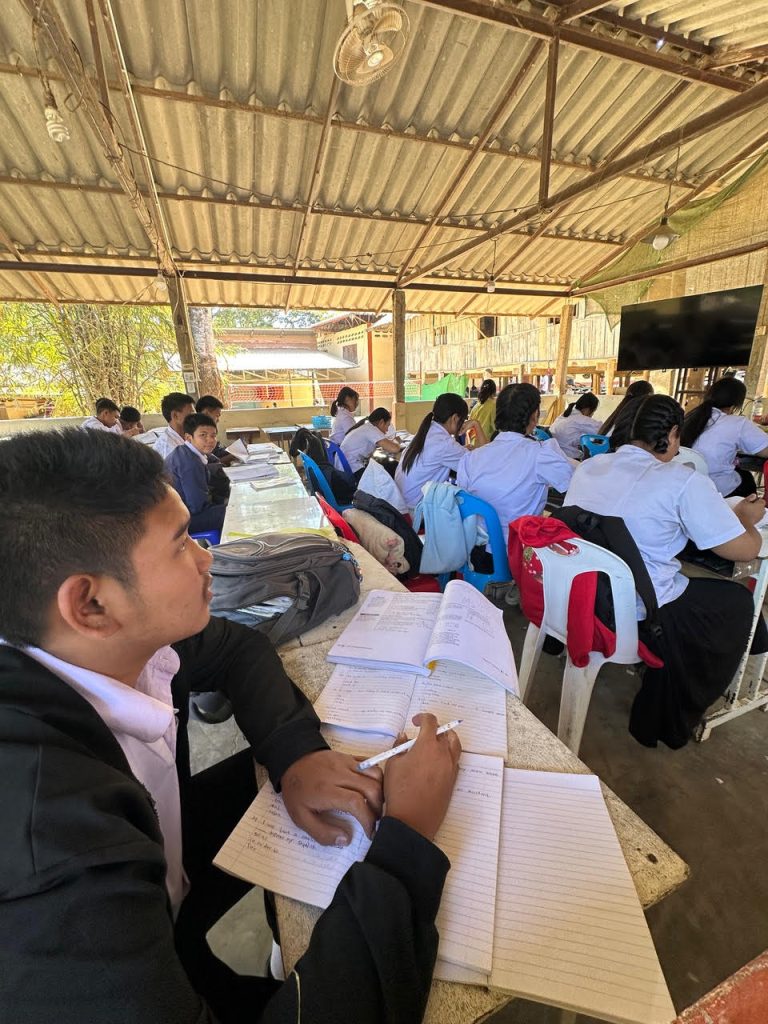

It is the end of the dry season and fields are ready for planting. Ficus and giant tamarinds line the two-lane highways. Min Thu Nya and a friend who drives the car pull up at the New Blood Learning Center, a school for 1500 displaced migrant children. It is one of several schools and organizations supported by the pro-democracy monks, with whatever donations they can help collect. This school has boarding for 200 children either orphaned or otherwise separated from their families. Families pay $3 a month if they can afford it. Teachers volunteer or work for a small salary, teaching grades K-5, then a GDE program, followed by the Cambridge program for English proficiency. Older students also learn agricultural skills, growing chili plants for the school kitchen and to sell for school income.

Another group of refugees includes former pro-democracy fighters who lost a limb in the war against the Myanmar regime. They live in a large, safe house, some with a wife and child families. They roll in wheelchairs and lift weights, waiting for prosthetic limbs fitted for them in Thailand and, hopefully, made in the United States.

***

Today Myanmar’s government in exile, the National Unity Government (NUG), opposes the military dictatorship but receives weak support from the international community. East Timor is the only nation that recognizes the NUG and speaks for them in the United Nations.

In Myanmar, a widespread Civil Defense Movement, the Peoples Defense Forces, and a coalition of armed ethnic organizations surround the military government, which controls only 20% of Myanmar.

“The army must force their own soldiers to fight by holding families hostage or making them serve as porters carrying heavy loads,” says one of Min Thu Nya’s friends.

China provides arms to both sides in Myanmar’s civil war. The regime gets attack jets and heavy weapons through official military sales. Illegal weapons trading supplies small arms for the army, and the armed groups that surround it.

“China can do whatever they want to support the regime. They are very clever,” says Min Thu Nya.

As a Buddhist monk, Min Thu Nya’s three choices did not include fighting.

“At the same time, we believe the people will win,” he says. “I never worry. My mind is not full of worry. I live my practice in this time, this second. I want to be happy.”

“Freedom would come faster if the international community would support us,” he adds.

Min Thu Nya’s Facebook page often displys a colorful banner with a blessing: “May you both physically and mentally stay away from danger and be healthy and wealthy. May you be a revolutionist who can be free from violence and evil.”

Larry Steele is a Shambhala meditator, teacher and long-ago international business person. He has known Min Thu Nya for seven years and recently visited him in Mae Sot.