Thursday

Community ArticlesBuddhism and Nonviolent Communication

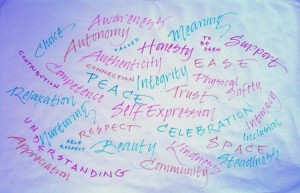

“Beautiful Needs” calligraphy created by Barbara Bash, www.barbarabash.com. Courtesy of Roberta Wall, www.steps2peace.com

Written for the Dot by Jason Leslie

Openness is not a matter of giving something to someone else, but it means giving up your demand and the basic criteria of the demand … It is learning to trust in the fact that you do not need to secure your ground, learning to trust in your fundamental richness, that you can afford to be open. This is the open way. — Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

I first encountered Nonviolent Communication (NVC) during a short afternoon workshop as part of a month-long course on career exploration and development. At the time, it was merely a curiosity for me. NVC seemed like just another tool in the self-help box—a clunky tool that felt overly artificial because of the cumbersome “I” statements and other expressions it required. I was far more enamored with meditation practice, and the stillness and clarity that it cultivated within me.

Editor’s Note: We are currently on hiatus from publishing new articles; in the meantime, please enjoy this classic item reprinted from our back issues.

But as a practicing lawyer, dealing in conflict as a trade, I eventually found myself yearning to connect what I was learning on the cushion with the rough and tumble of the challenging interactions in my professional and even my personal life. Buddhism provides some wonderful methods for doing this, and in embracing those teachings I found myself being drawn to various forms of conflict resolution and peace building. These explorations led me back to NVC, and this time, the parallels between the teachings of the Buddha and of Dr. Marshall Rosenberg, the founder of NVC, have been striking.

The purpose of NVC, in Dr. Rosenberg’s words, is to allow people to communicate in a way “that leads us to give from the heart, connecting us with ourselves and with each other in a way that allows our natural compassion to flourish.” Sound familiar? To me, at least, this is basically a description of getting in touch with basic goodness and creating enlightened society.

NVC guides us to focus our consciousness on four areas. First, we observe what is happening within and around us without judging or evaluating. Second, we identify what we are feeling, as opposed to what we are thinking or how we are interpreting the situation. Third, we uncover the needs that are at the root of our feelings and express them clearly. Fourth, we request that another person take an action that might fulfill our needs and enrich our lives, without demanding that the person satisfy our request in order to avoid judgment or punishment from us.

When first learning NVC, these four steps are often made very explicit. As a simple example, I might say, “When you slam the door, I feel frightened because I need peace and quiet in my environment. Would you mind closing the door more lightly next time?” But as I learned in that afternoon workshop years ago, speaking this way can seem very strained at first. Doing so in a situation with a high emotional charge is even more difficult. However, the exercise of even just trying to express oneself in these terms—sticking to observations, feelings, needs, and requests—can be very revealing, and also naturally leads to a very high degree of mindfulness.

Roberta Wall, a lawyer and a Buddhist in the Zen tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh, works in the court system in New York State as a law guardian for children and youth, and also teaches NVC. She sees the “distinction between needs and strategies” which NVC draws to be “a doorway to the practice of non-attachment.” By drawing our attention to the needs we feel and whether we are “requesting” or “demanding” that others meet those needs, NVC helps us develop equanimity and see new and more harmonious ways to get our needs met. The tools also help us to abandon our desperate search for ground and our imposition of an agenda onto the situation, encouraging us to trust in the compassion of others. If our request is denied, NVC suggests that we focus on what the other person is feeling and needing so that we can work intelligently and compassionately with them. As Roberta explains, “Different needs are not in conflict with each other. That perception is an illusion that attaches us to strategy. NVC shows us that all needs can matter.”

Roberta frequently collaborates with Barbara Bash, a Shambhala Buddhist illustrator and writer who developed an interest in NVC several years ago as a skill set for helping to resolve conflicts within her sangha. Barbara now runs regular NVC sessions at Sky Lake Lodge in New York State and teaches NVC to inmates at a local prison. When I remarked to Barbara how difficult it is to apply NVC despite its apparent simplicity, she immediately sympathized and suggested that it is important to learn how to use NVC with yourself before using it with others. Without a solid understanding of your own feelings and needs, it is not possible to get very far in relating to the feelings and needs of others. To me, this sounded a lot like the interaction between the hinayana and mahayana in the Buddhist system.

Barbara emphasized that NVC is very much meditation in action, or more precisely, “meditation in relationship,” requiring a shift from moment-by-moment awareness of the breath to moment-by-moment attunement to the feelings and needs of oneself and others. If attention can stay on those feelings and needs, rather than drifting off into demands and judgments, then compassion naturally arises. Just as with meditation, using NVC requires effort to keep one’s focus on track, but the benefits are ultimately self-arising.

And also like meditation, NVC is a lifelong practice. As I learned from my initial workshop experience, a few hours of training may just scratch the surface and provide only a hint of the potential in the method. Of course, it is possible to go on retreat and learn NVC over a week, or even a weekend, and get some lasting benefit. However, the true transformative impact happens only over time, generating changes at a very deep and non-conceptual level. Such changes ultimately require patience, exertion, discipline, and other qualities cultivated by the aspiring bodhisattva.

Oct 19, 2018

Reply

Dear Jason – This is delightful to read again. Don’t recall when you wrote this. It sure holds up ! Was it at a Sky Lake workshop when we met? Am continuing on with this good work, doing a lot of circle work at Sky Lake. Getting “in the room” together seems crucial these days: heartening, strengthening, building compassion for oneself and others. Thanks again for writing this!